Lecture 11: Dynamic Programming¶

CBIO (CSCI) 4835/6835: Introduction to Computational Biology

Overview and Objectives¶

We've so far discussed sequence alignment from the perspective of distance metrics: Hamming distance and edit distance in particular. However, on the latter point we've been coy; how is edit distance actually computed for arbitrary sequences? How does one decide on the optimal alignment, particularly when using different scoring matrices? We'll go over how all these concepts are incorporated around the concept of dynamic programming, and how this allows you to align arbitrary sequences in an optimal way.

By the end of this lecture, you should be able to:

- Describe how dynamic programming works and what its runtime properties are

- Relate dynamic programming to the Manhattan Tourist problem, and why it provides the optimal solution

- Compute the edit distance for two sequences

Part 1: Change, Revisited¶

Remember the Change Problem?

Say we want to provide change totaling 97 cents.

Lots of different coin combinations you could use, but if we wanted to use as few coins as possible:

- 3 quarters (75 cents)

- 2 dimes (20 cents)

- 2 pennies (2 cents)

Two Questions¶

1: How do we know this is the fewest possible number of coins?

2: Can we generalize to arbitrary denominations (e.g. 3 cent pieces, 9 cent pieces, etc)?

Formally¶

Problem: Convert some amount of money $M$ into the given denominations, using the fewest possible number of coins.

Input: Amount of money $M$, and an array of $d$ denominations $\vec{c} = (c_1, c_2, ..., c_d)$, sorted in decreasing order (so $c_1 > c_2 > ... > c_d$).

Output: A list of $d$ integers, $i_1, i_2, ..., i_d$, such that

$c_1i_1 + c_2i_2 + ... + c_di_d = M$

and

$i_1 + i_2 + ... + i_d$ is as small as possible.

Yay, Equations...¶

Let's look at an example.

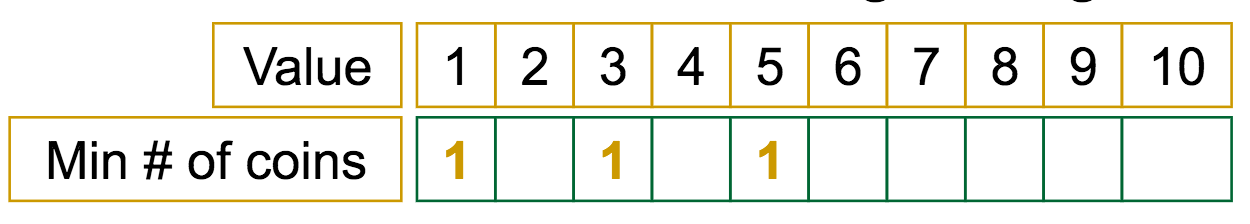

- Given: The denominations $\vec{c} = (1, 3, 5)$ (so $d = 3$)

- Problem: What is the minimum number of coins needed to make each of the following values for $M$?

(hopefully, you can see only 1 coin each is needed to make the values $M = 1$, $M = 3$, and $M = 5$)

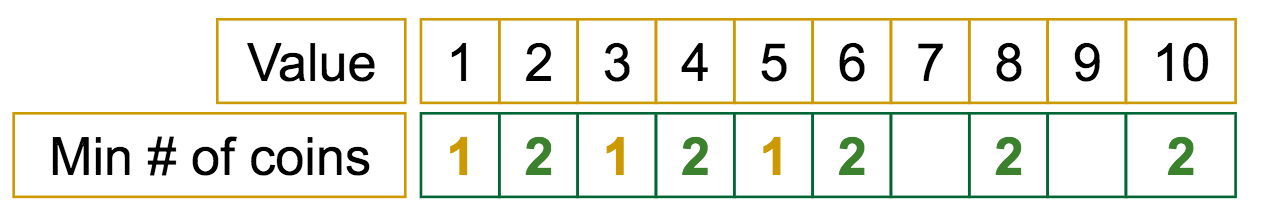

How about for the other values?

You'll need 2 coins for $M = 2$, $M = 4$, $M = 6$, $M = 8$, and $M = 10$.

What are the coins?

See any patterns yet?

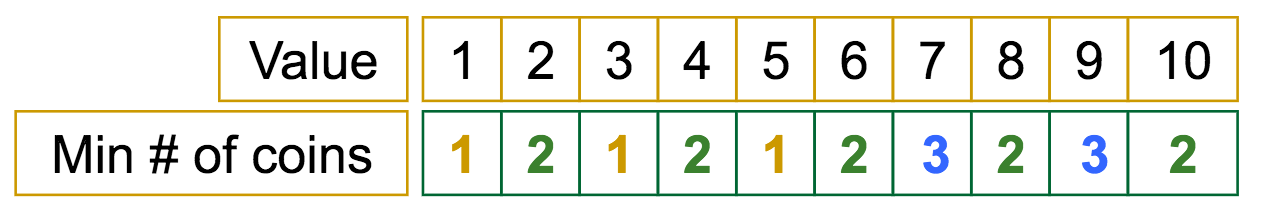

How about the remaining values?

3 coins each for $M = 7$ and $M = 9$.

See the pattern yet?

Recurrence Relations¶

A recurrence relation is, generally speaking, an equation that relies on previous values of the same equation (future values are functions of previous values).

What examples of common problems fall under this category?

- Differential Equations

- Fibonacci Numbers

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21...

$f(n) = f(n - 1) + f(n - 2)$

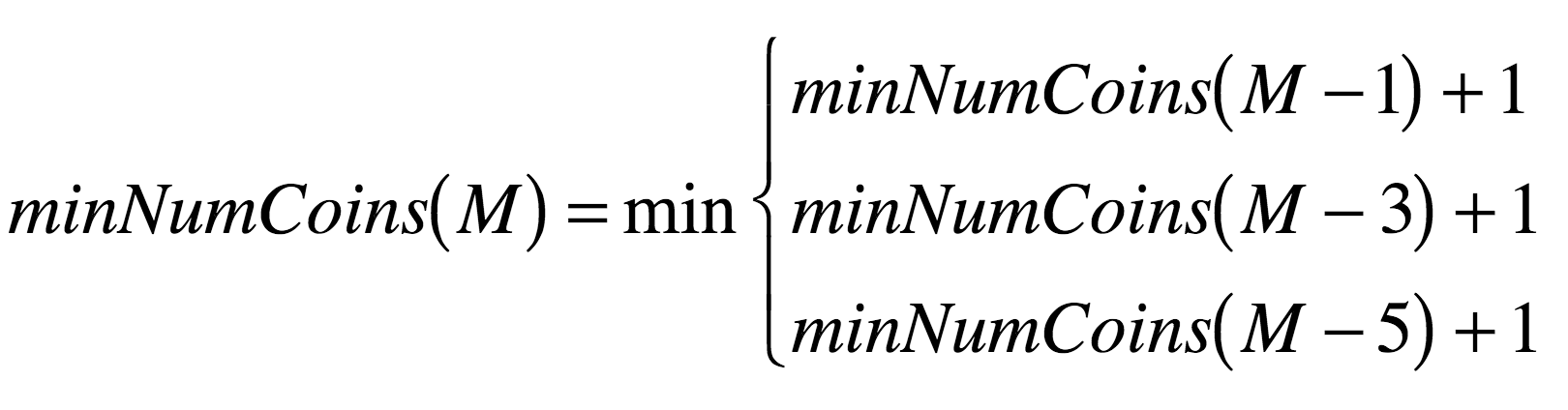

So, for our example of having 3 denominations, our recurrence relation looks something like this:

- If $M = 1$, $M = 3$, or $M = 5$, $minNumCoins$ is 0 + 1, so we get 1. These "special cases" are referred to in recurrence relations as base cases.

- If $M = 2$, $M = 4$, $M = 6$, or $M = 8$, these all reduce to the base cases, with an added +1, so each of these evaluates to 2.

- Finally, if $M = 7$ or $M = 9$, these are reduced to one of the above cases first (+1), then one of the base cases (+1), for a total of 3.

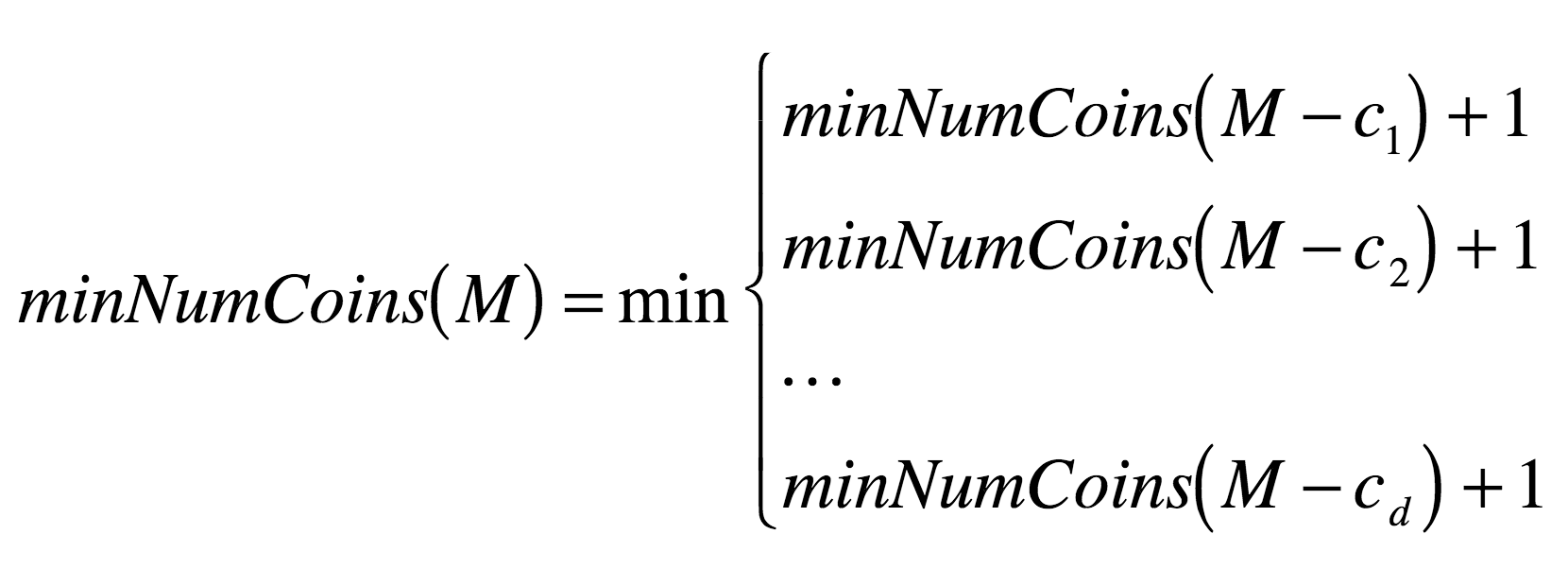

So, in general¶

What would this recurrence relation look like for the general case of $d$ denominations?

(see any problems yet?)

Example, Part Deux¶

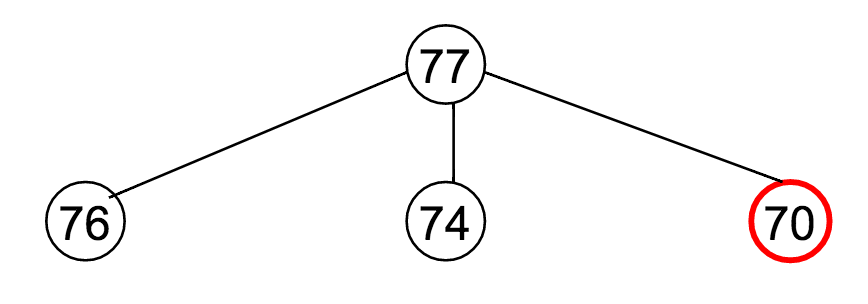

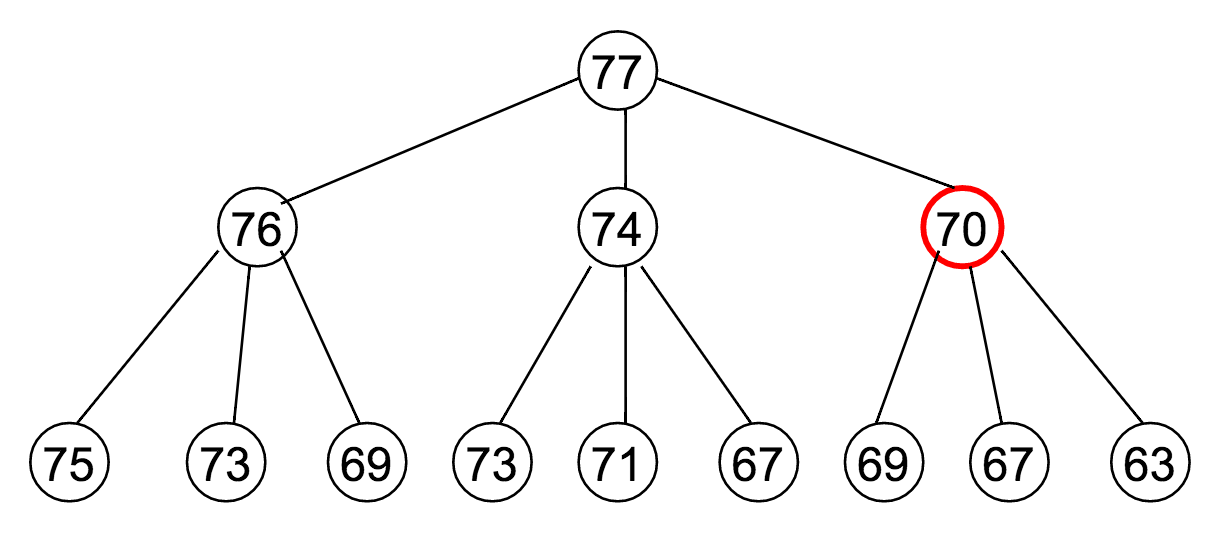

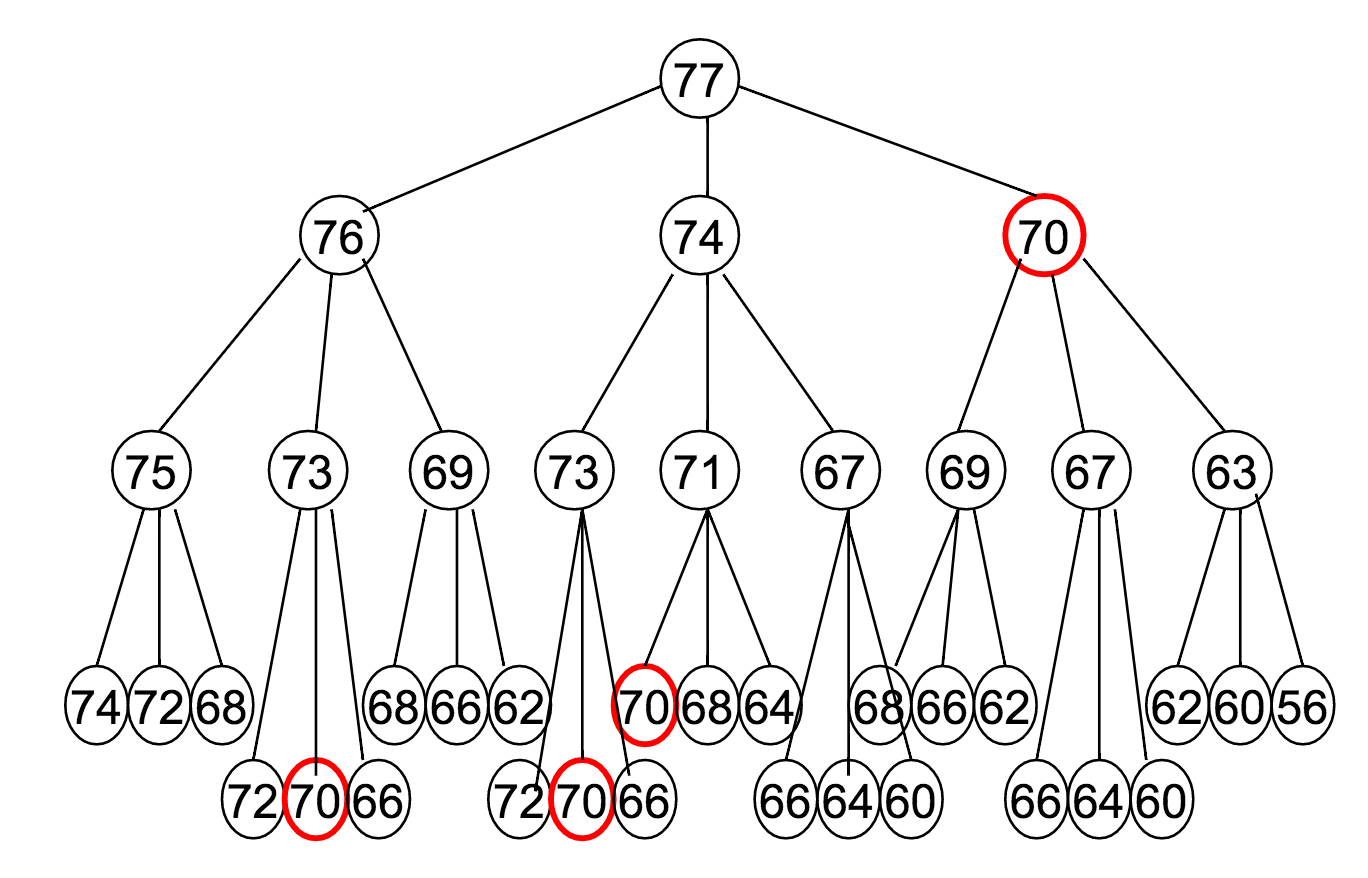

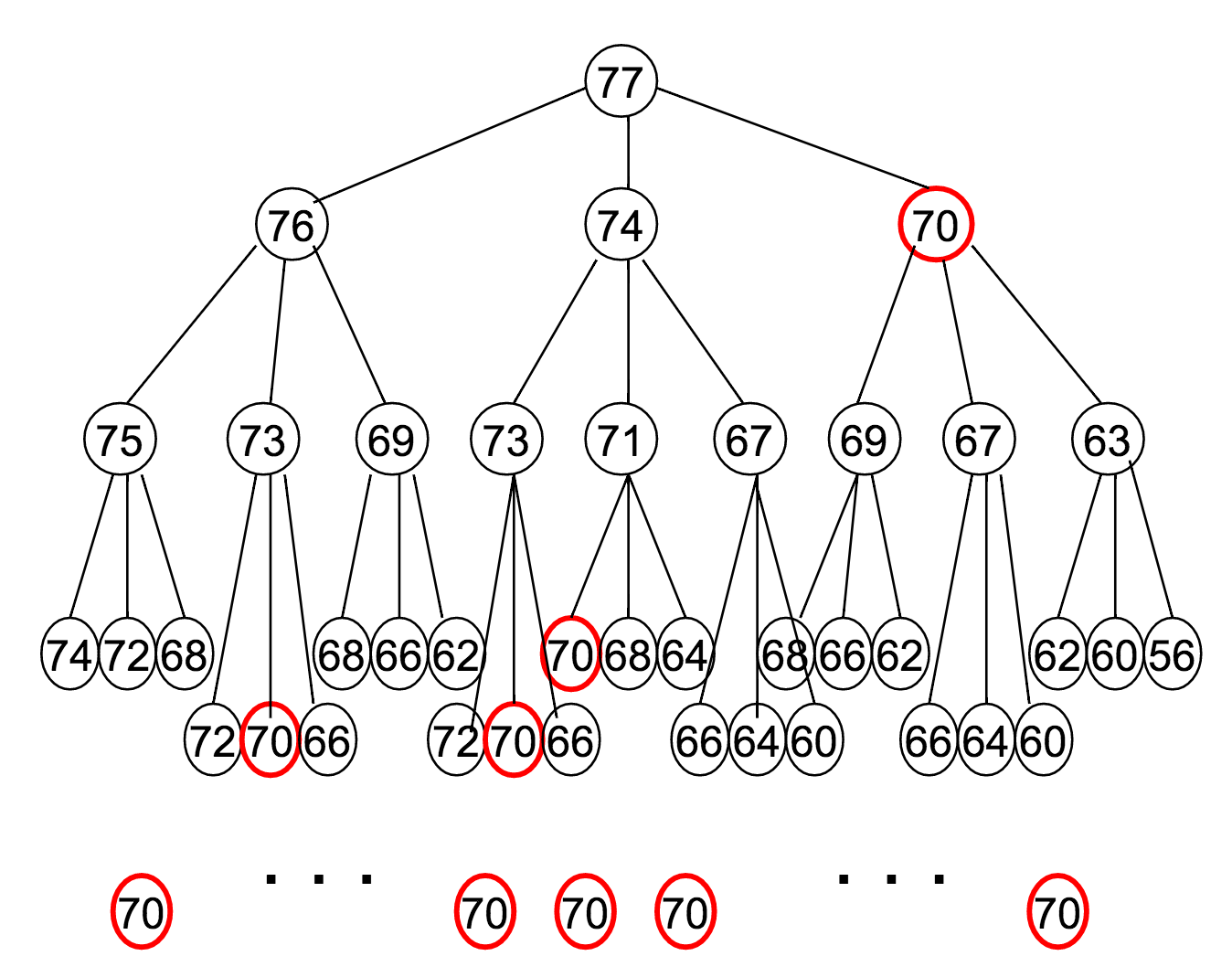

Let's say $M = 77$, and our available denominations are $\vec{c} = (1, 3, 7)$. How does this recurrence relation unfold?

Well...

Notice how many times that "70" appeared?

The reason it was highlighted in a red circle is to draw attention to the fact that it's being re-computed at every one of those steps.

So many repeated calculations!¶

At multiple levels of the recurrence tree, it's redoing the same calculations over and over.

- In our example of $M = 77$, $\vec{c} = (1, 3, 7)$, the optimal coin combination for 70 is computed 9 separate times.

- The optimal coin combination for 50 cents is computed billions of times.

- How about the optimal coin combination for 3 cents? o_O

How can we improve the algorithm so we don't waste so much time recomputing the same values over and over?

Part 2: Dynamic Programming¶

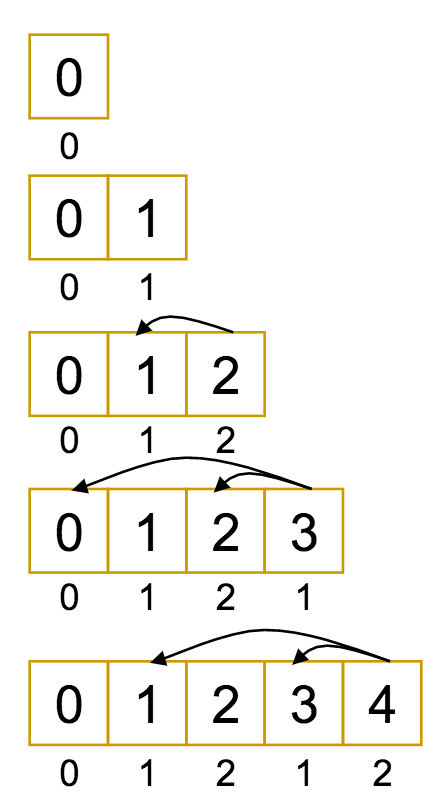

The idea is pretty simple, actually: instead of re-computing values in our algorithm, let's save the results of each computation for all amounts 0 to $M$.

Therefore, we can just "look up" the answer for a value that's already been computed.

This new approach should give us a runtime complexity of $\mathcal{O}(Md)$, where $M$ is the amount of money and $d$ is the number of denominations (what was the runtime before?).

This is called dynamic programming.

Let's look at a modification of the example from before, with $M = 9$ and $\vec{c} = (1, 3, 7)$.

If that looked and felt a lot like what we were doing before, that's not wrong!

Dynamic Programming does indeed closely resemble the recurrence relation it is intended to replace.

The difference is, with the recurrence, we had to constantly recompute the "easier" values farther down the tree, since we always started from the top.

With dynamic programming, it's the other way around: we start at the bottom with the "easier" values, and build up to the more complex ones, using the solutions we obtain along the way. In doing so, we avoid repetition.

Part 3: The Tourist in Manhattan¶

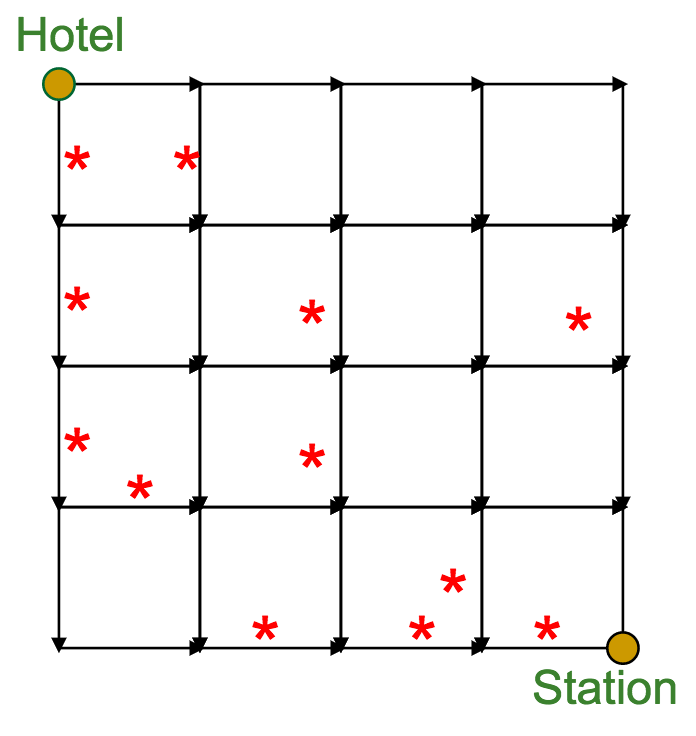

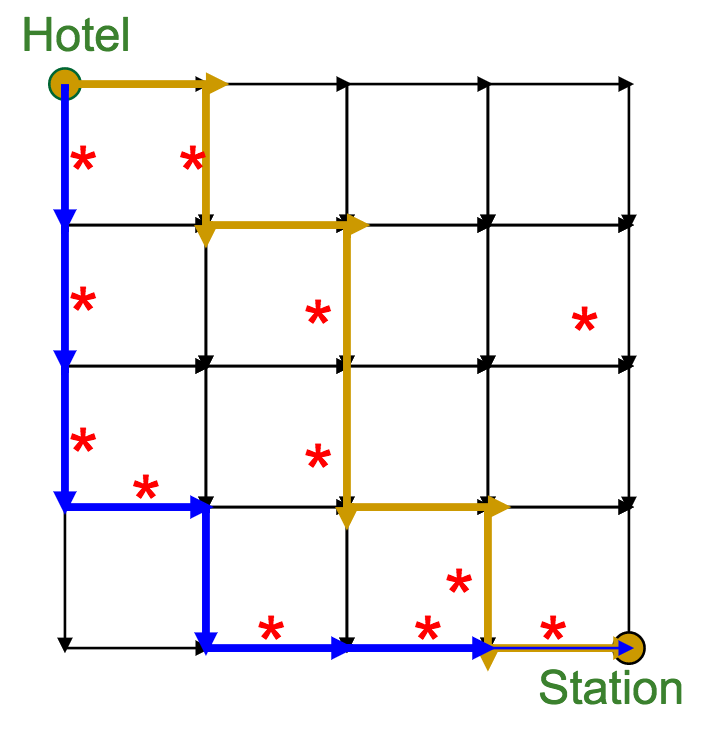

Imagine you're a tourist in Manhattan.

You're about to leave town (starting at the hotel), but on your way to the subway station, you want to see as many attractions as possible (marked by the red stars).

Your time is limited--you can only move South or East. What's the "best" path through town? (meaning the one with the most attractions)

Formally¶

Yes, the Manhattan Tourist Problem is indeed a formal problem from Computer Science, and specifically graph theory:

Problem: Find the optimal path in a [weighted] grid.

Input: A weighted grid $G$ with two labeled vertices: a source (the starting point) and a sink (the ending point).

Output: The optimal path through $G$, starting at the source and ending at the sink.

First attempt: the "greedy" approach¶

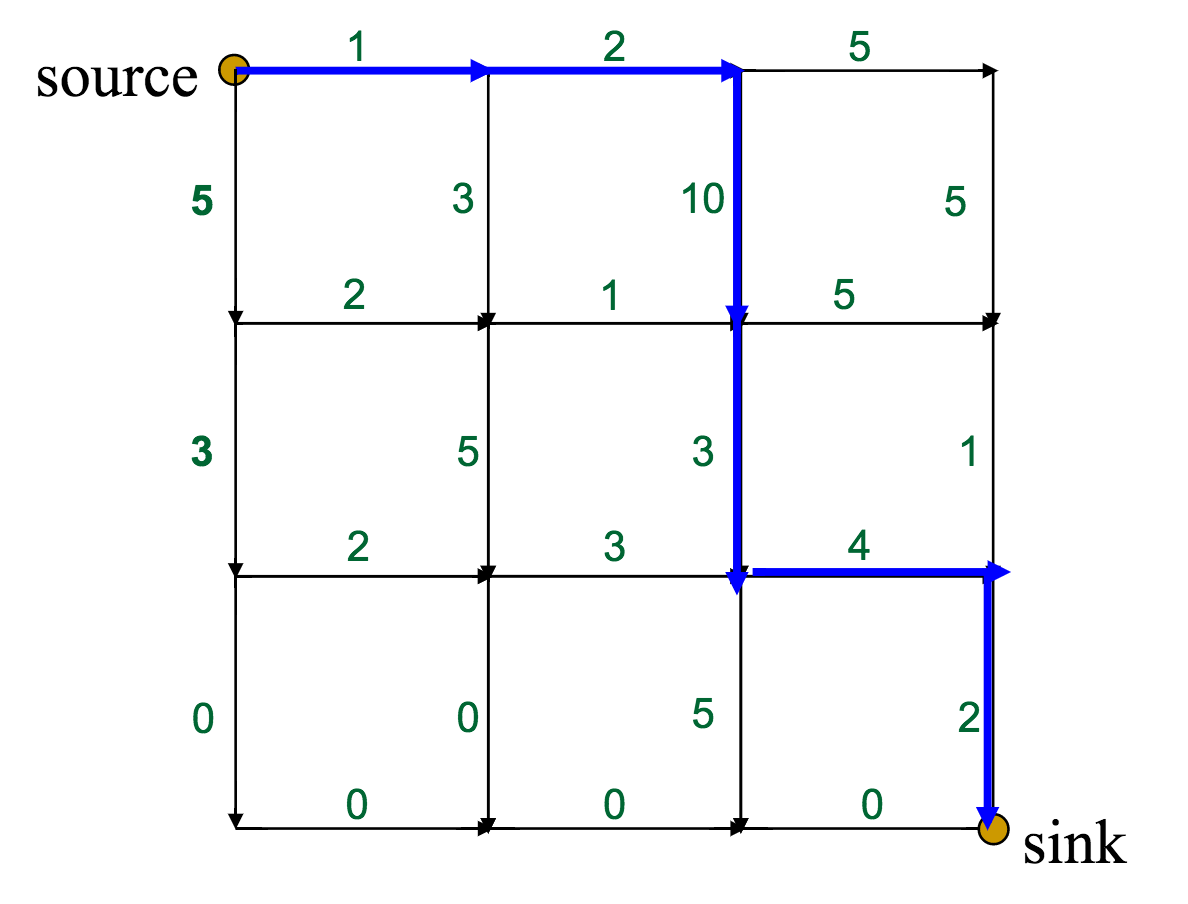

One reasonable first attempt, as I would have with the Change problem, would be a greedy approach: every time I have to make a decision, pick the best one available.

With the Manhattan Tourist Problem, this means that at each intersection, choose the direction (south or east) that gives me immediate access to the most attractions.

What's wrong with this approach?

It can miss the global optimum, if it chooses a route early on that diverts it away:

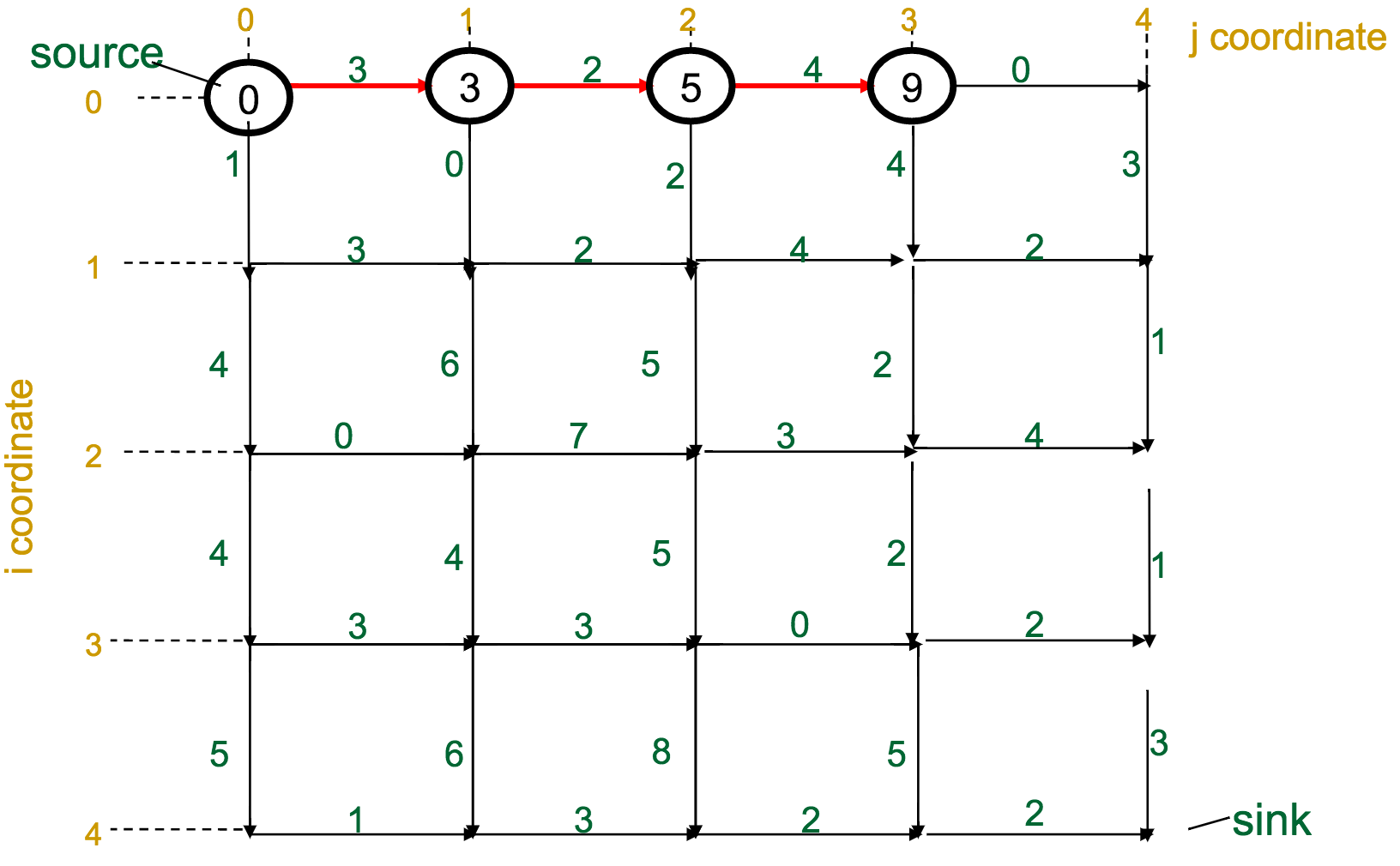

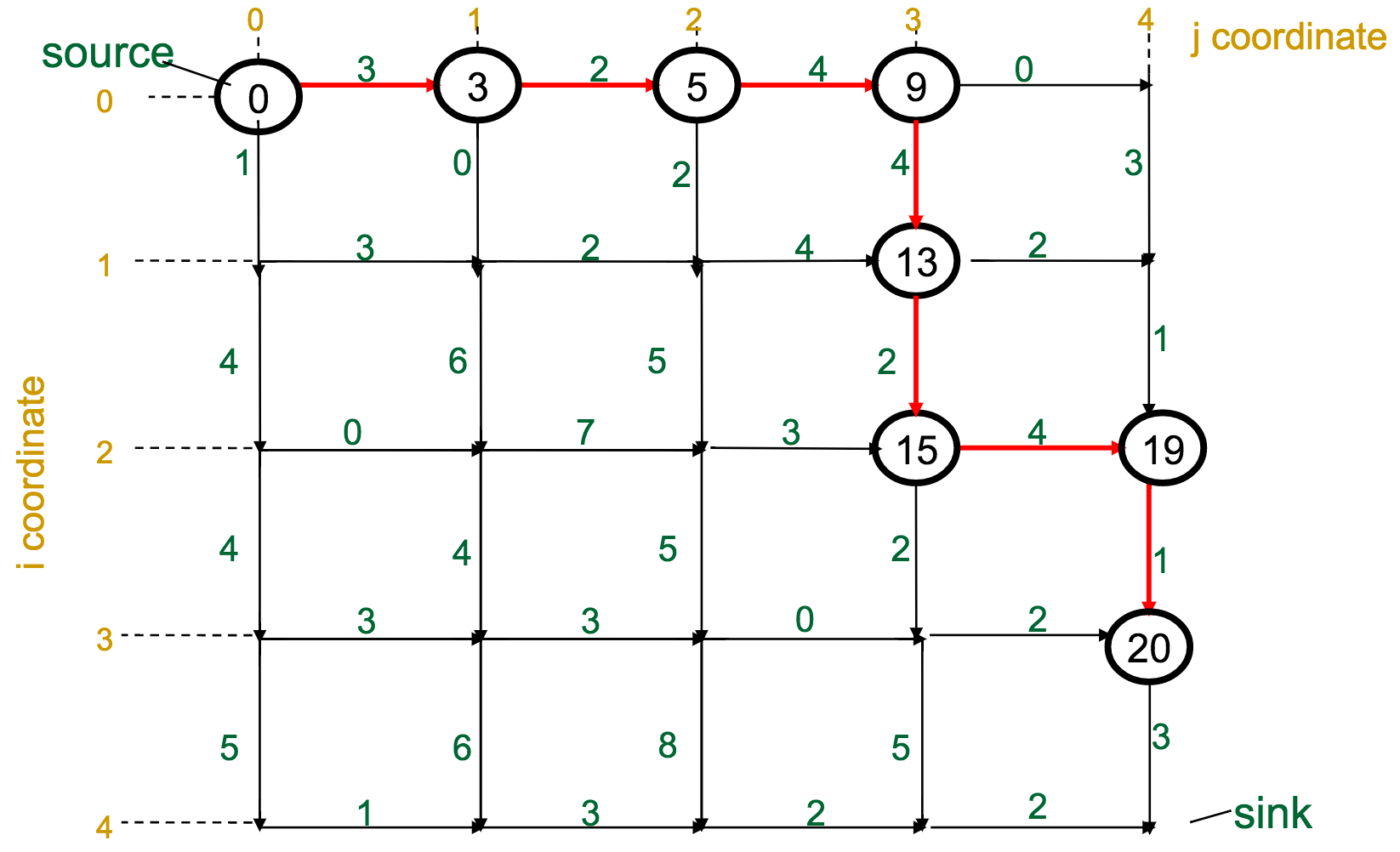

This is the optimal route, with a total weight of 22. However, what route would a greedy approach choose?

The red route has only a global weight of 18, but the initial choice at the source--between 5 and 1--will push the greedy algorithm off course.

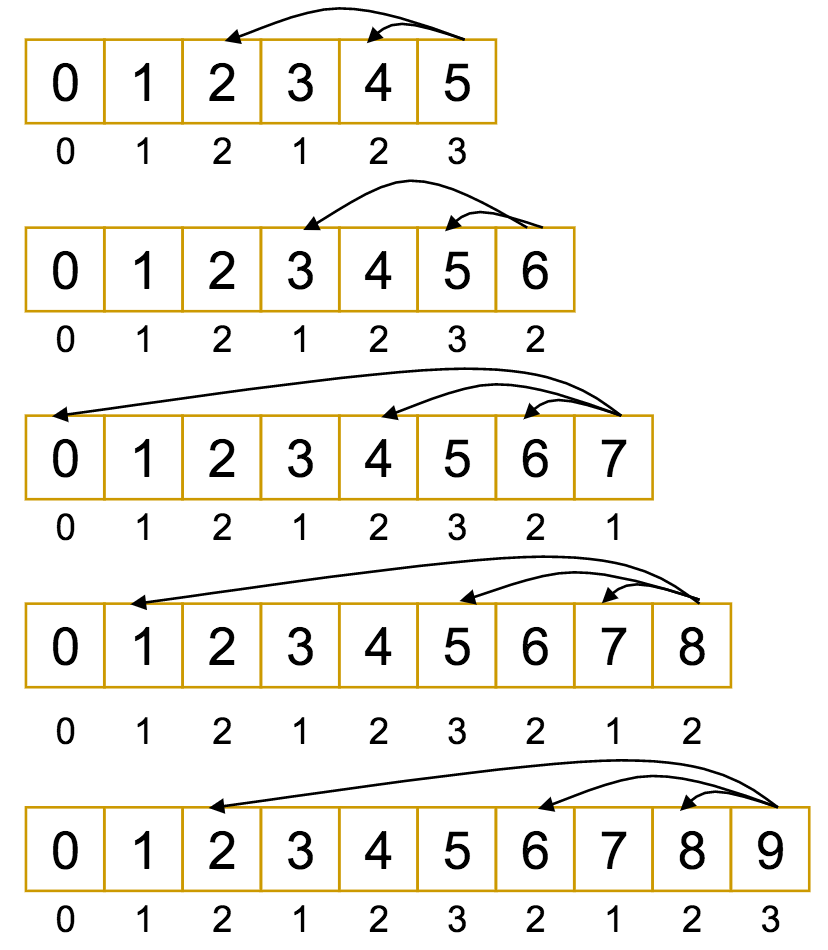

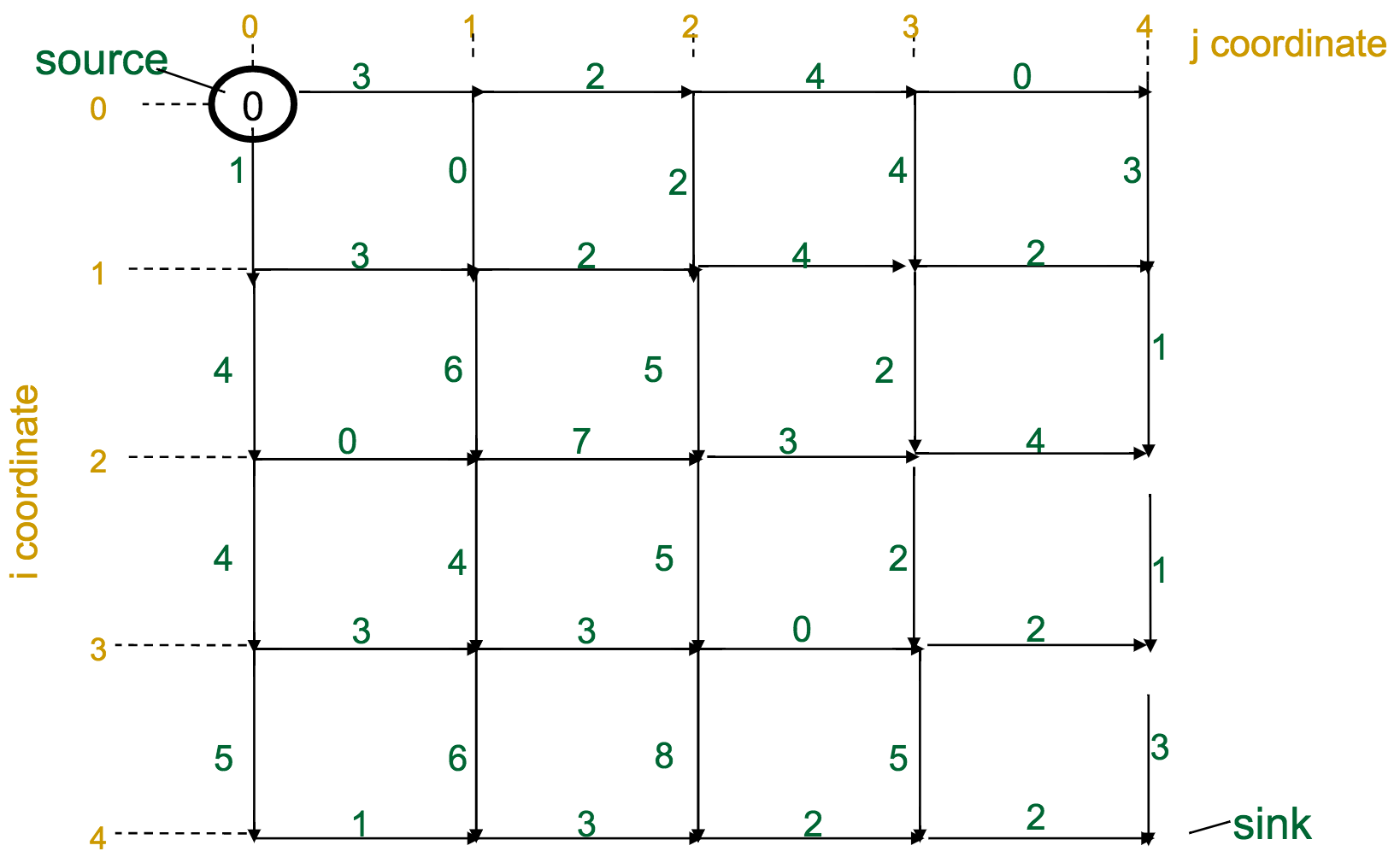

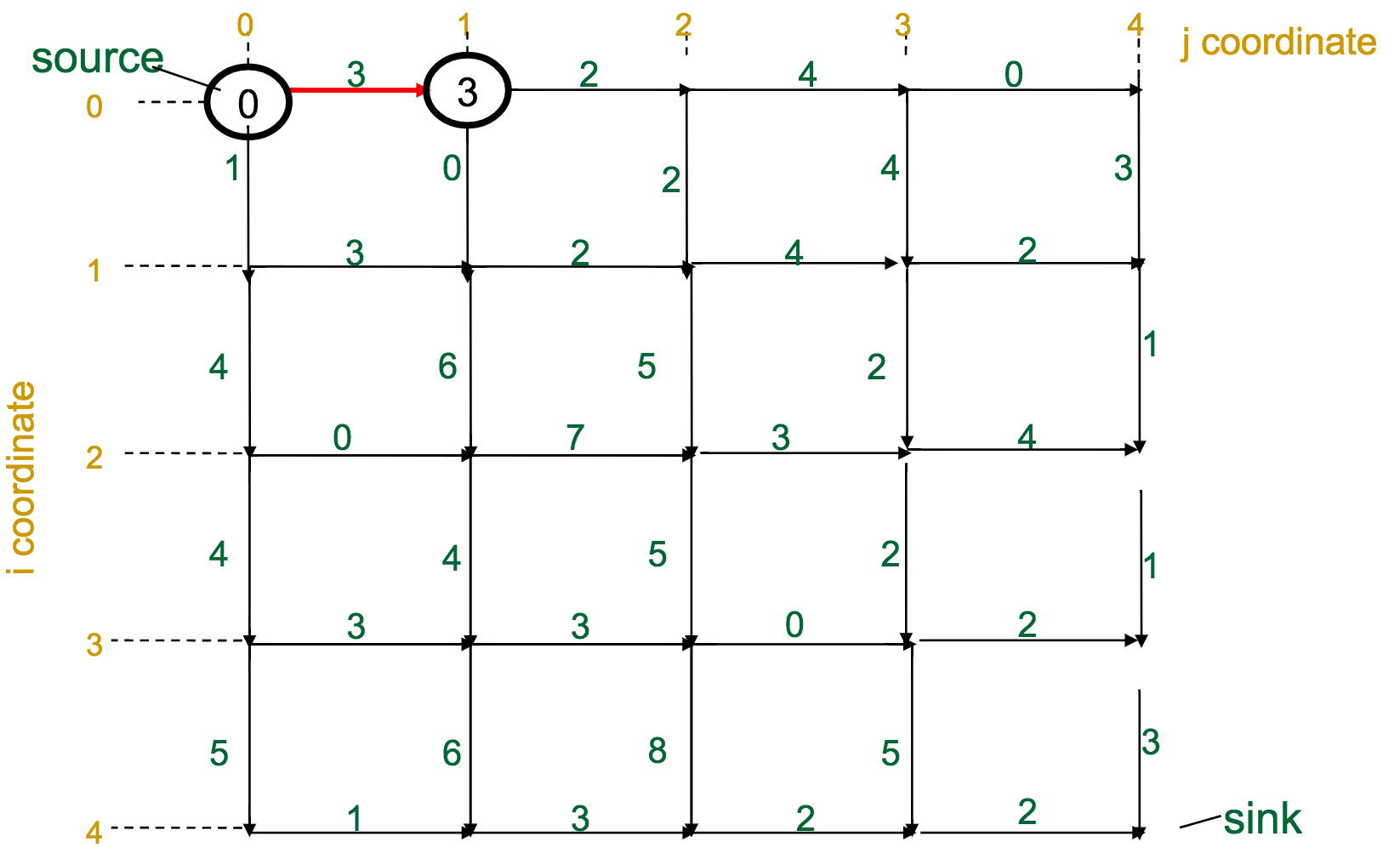

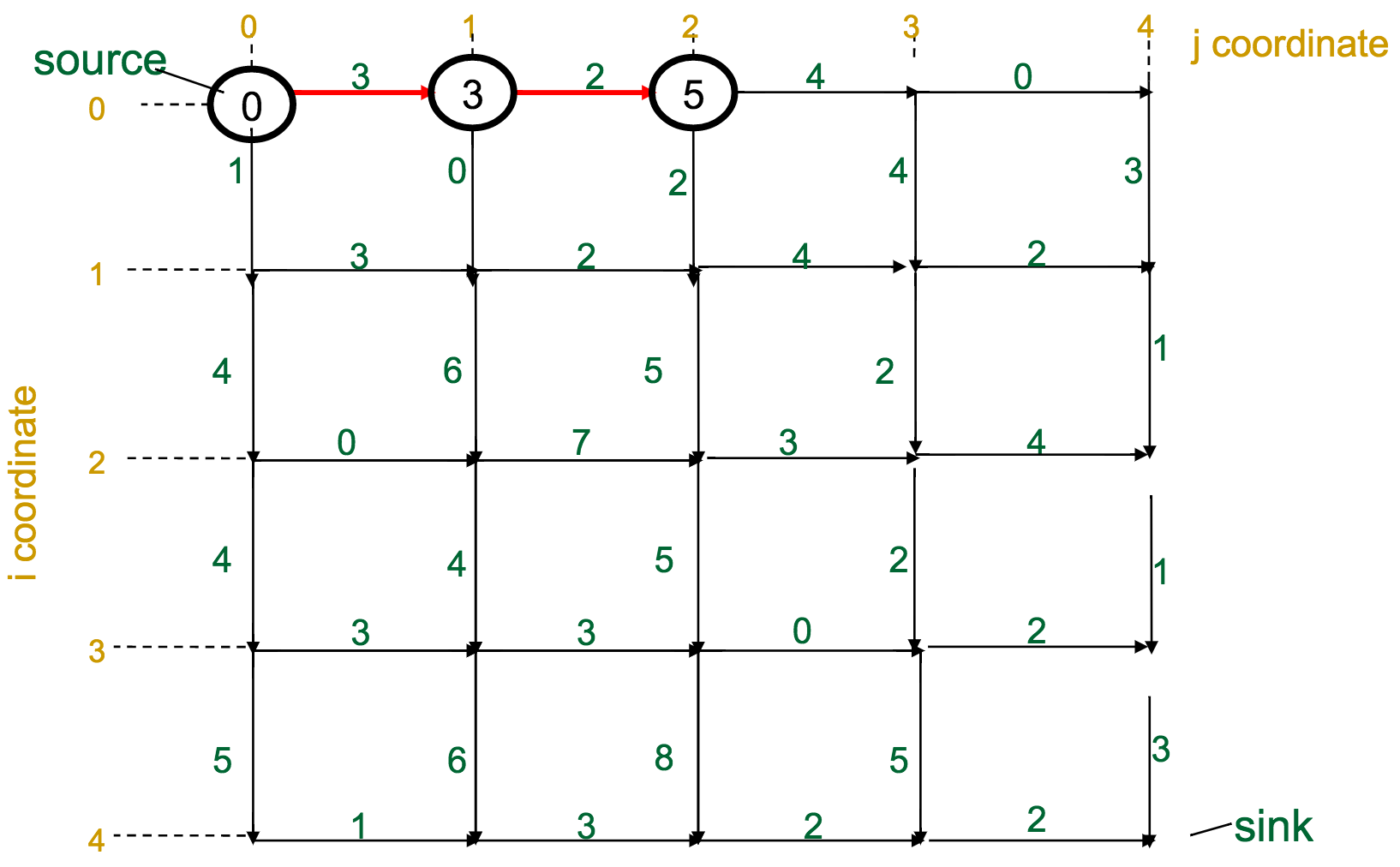

Dynamic Programming to the Rescue¶

Hopefully by now you're already thinking "this sounds like something dynamic programming could help with."

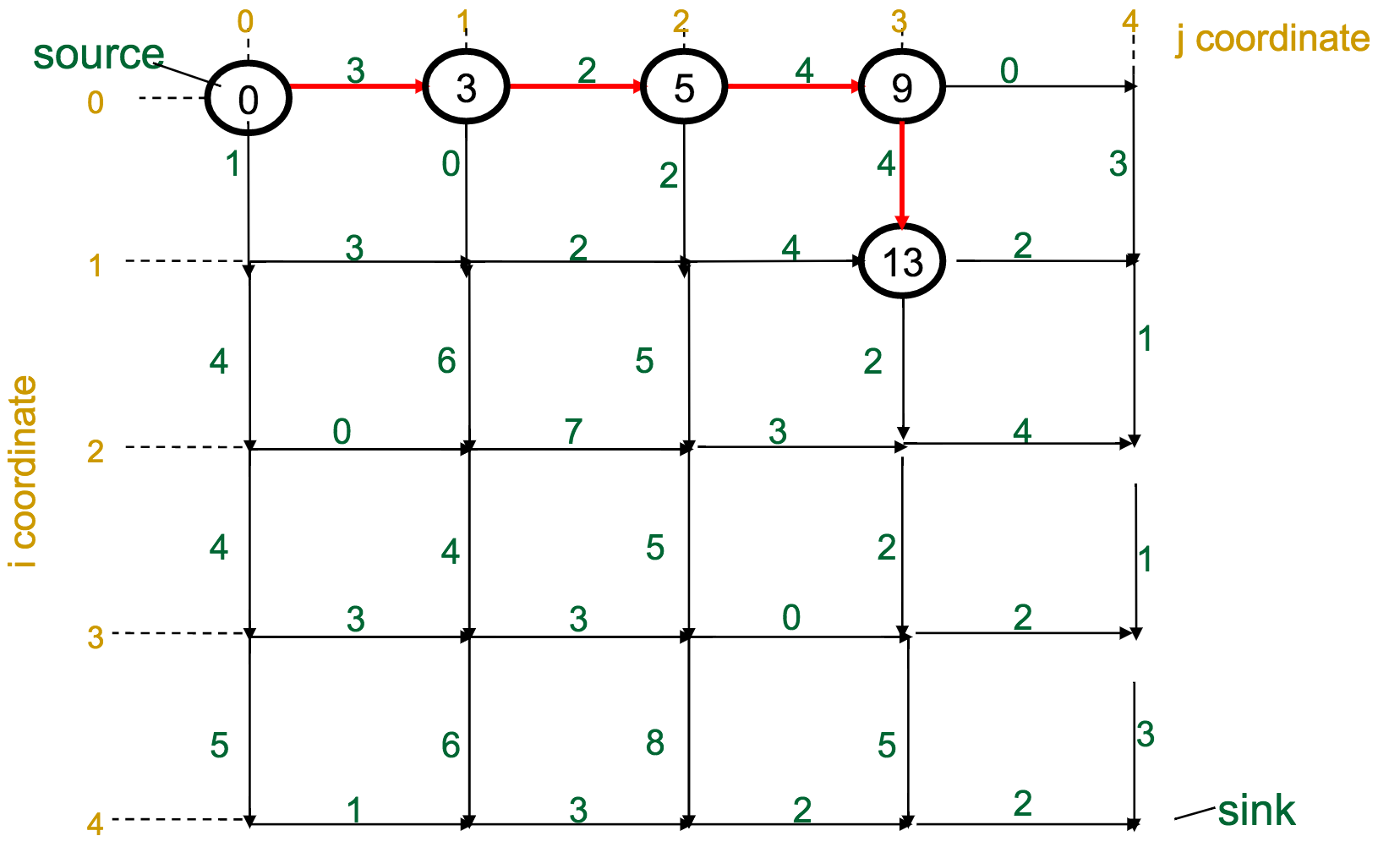

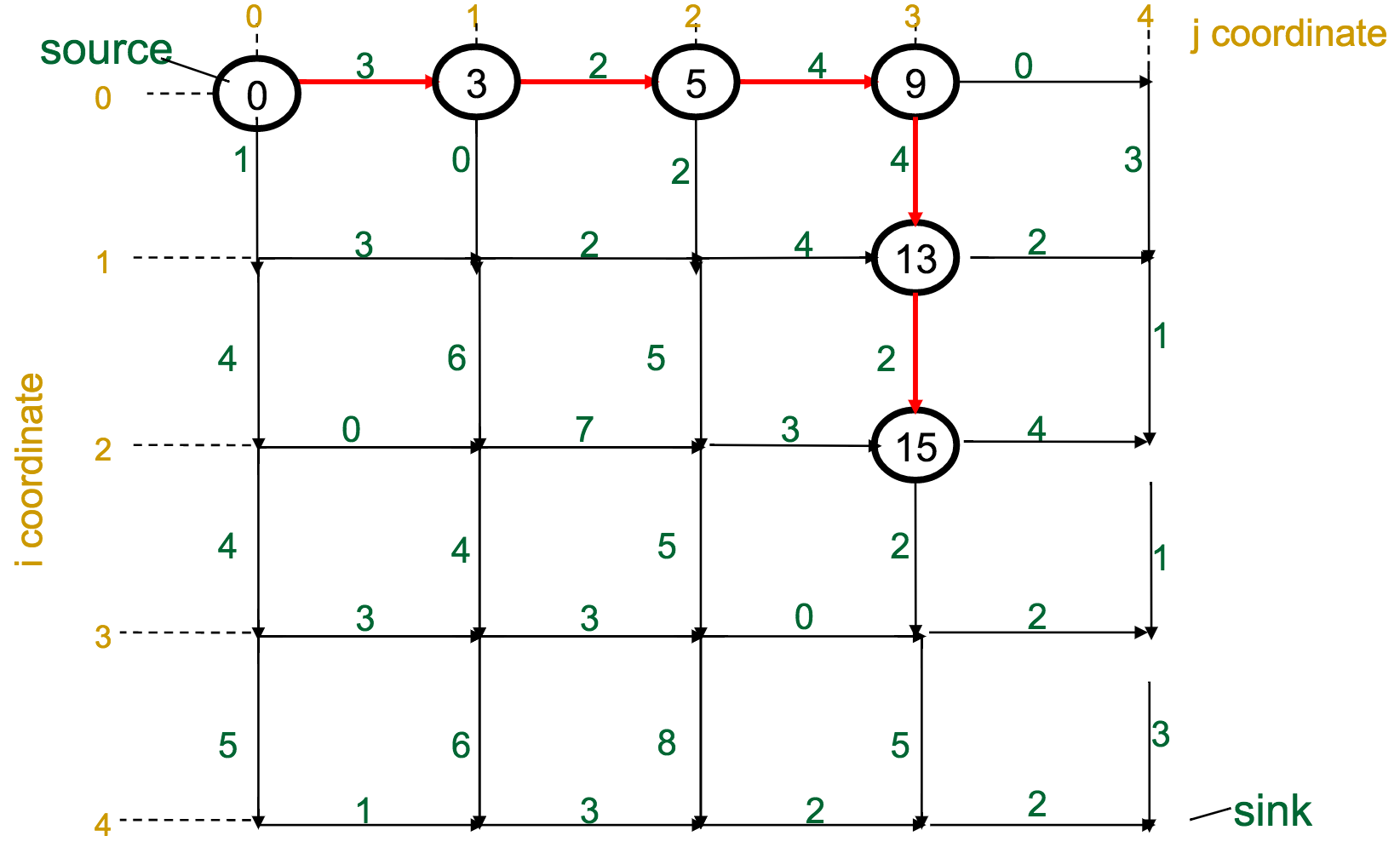

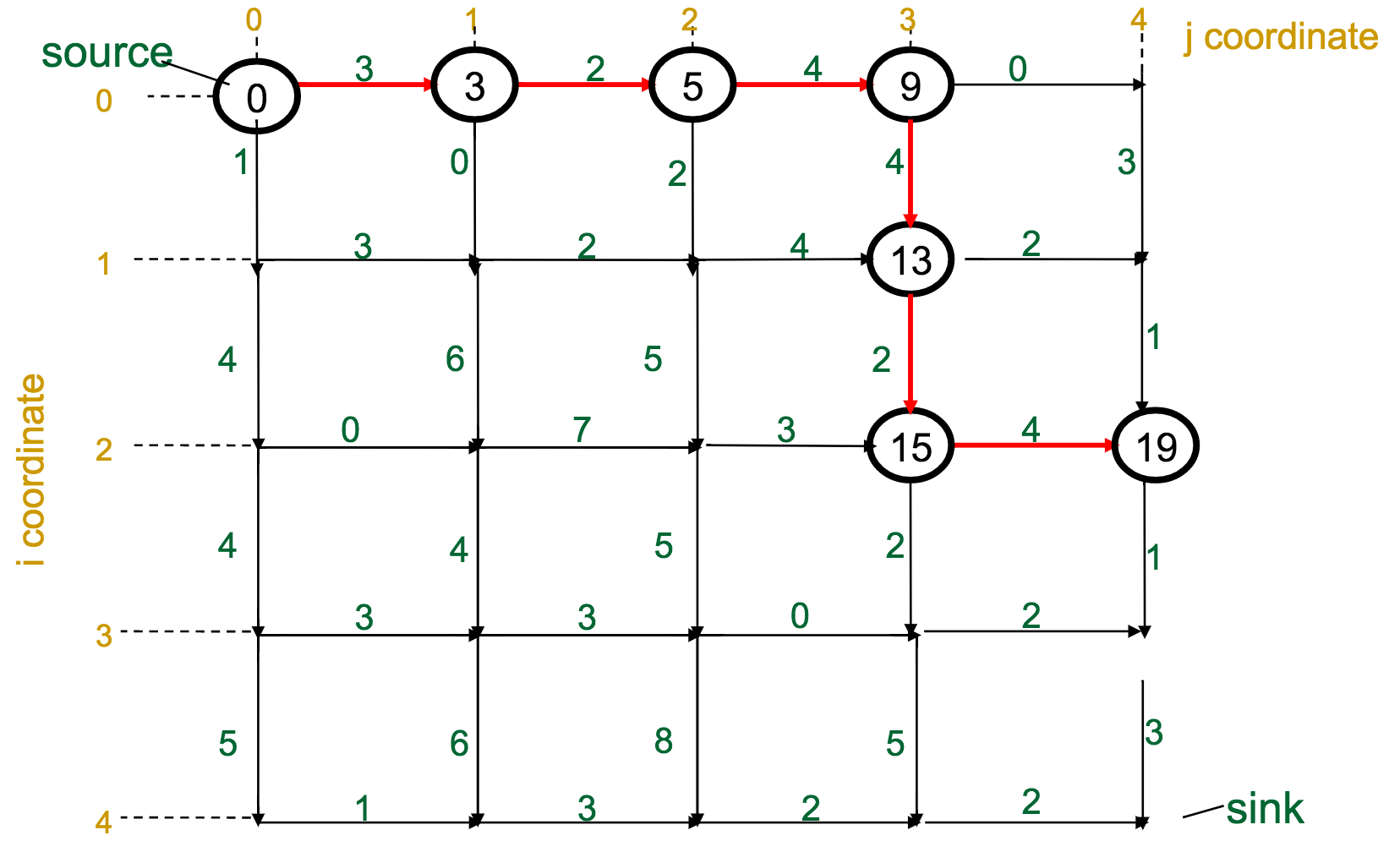

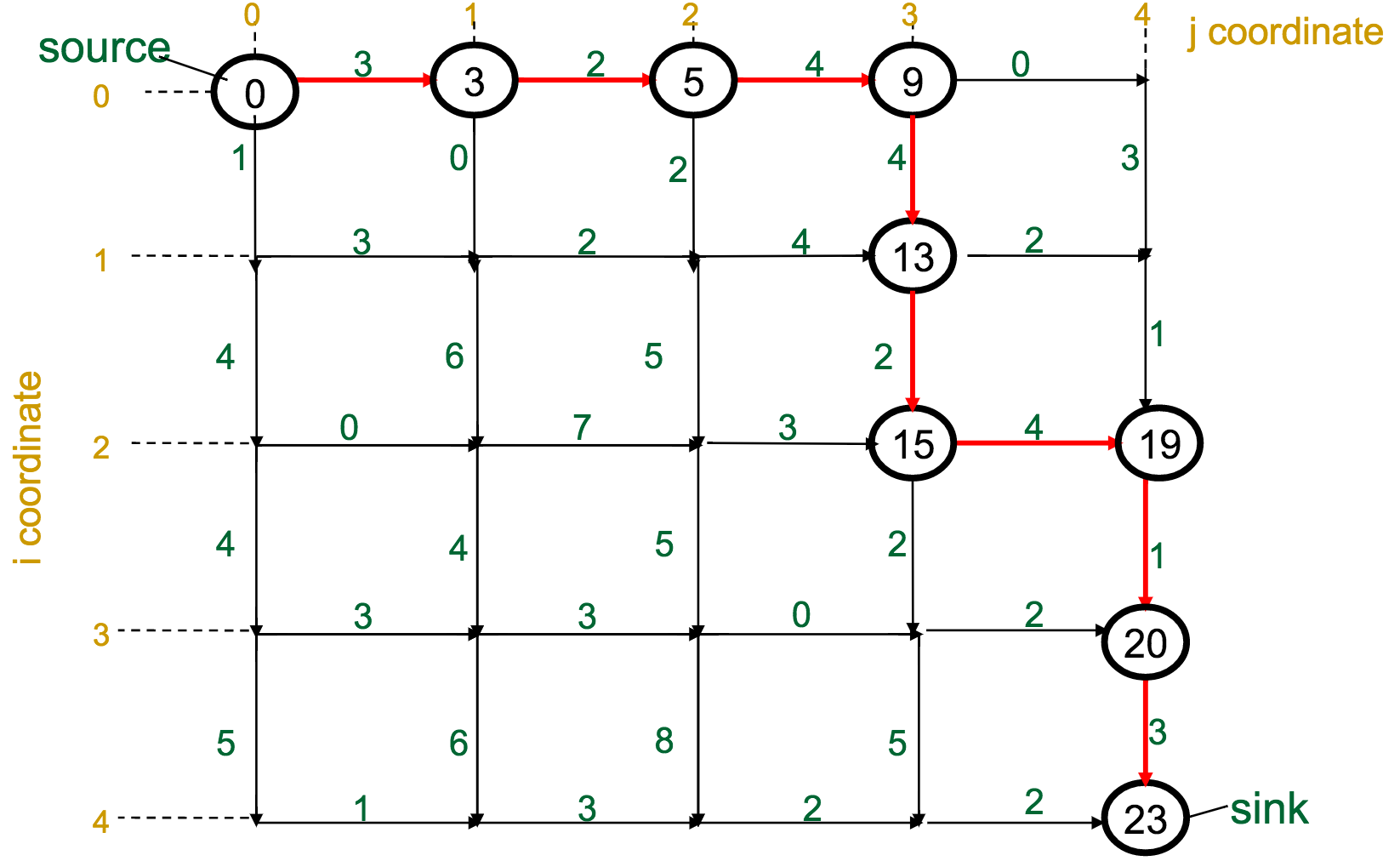

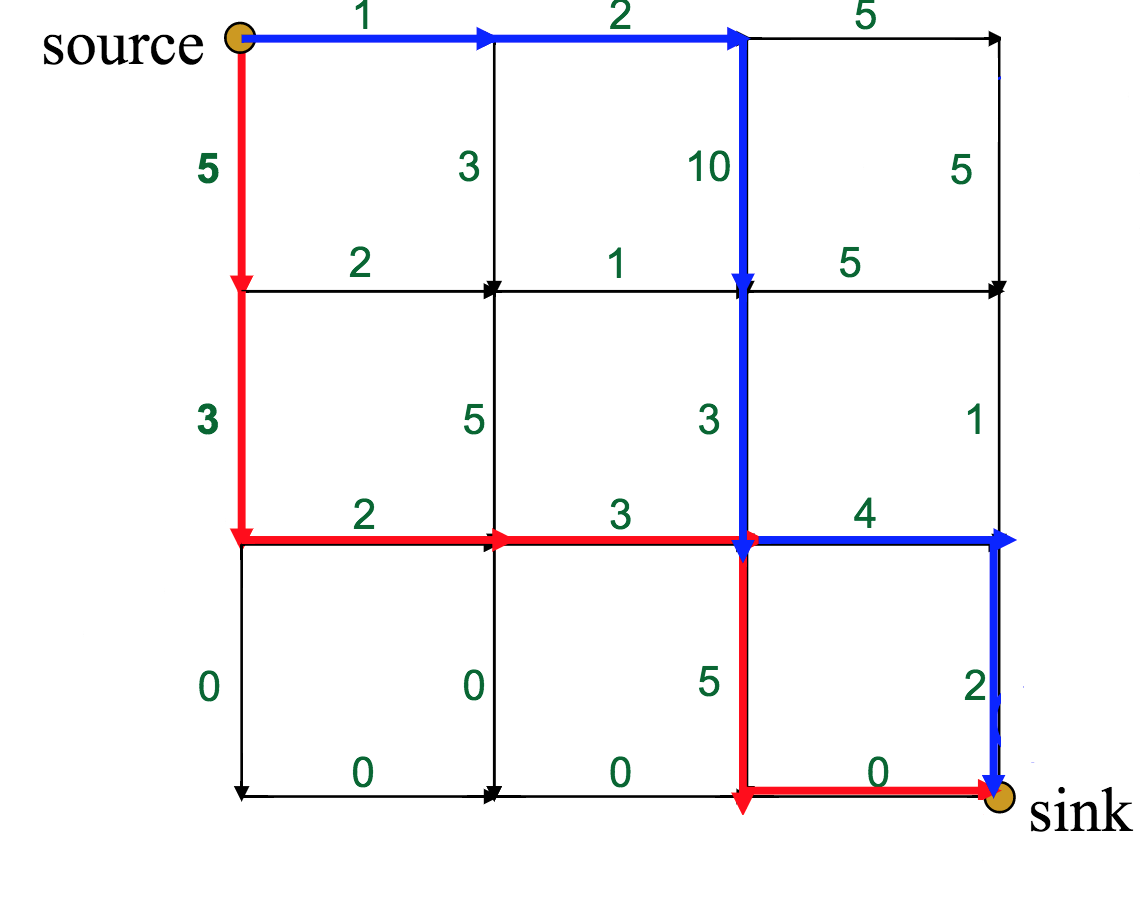

- At each vertex (intersection) in the graph, we calculate the optimal score to get there

- A given vertex's score is the maximum of the incoming edge weights + the previous vertex's score (sound familiar?)

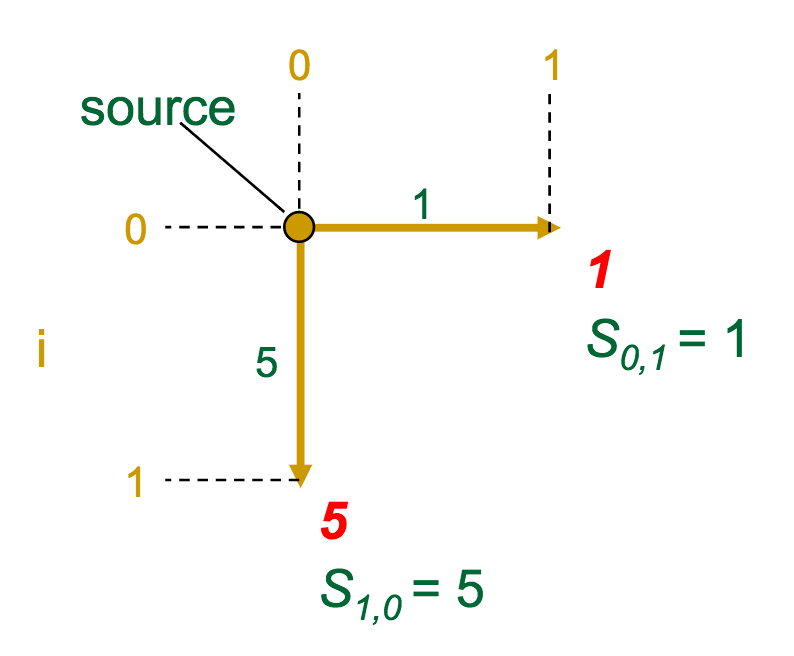

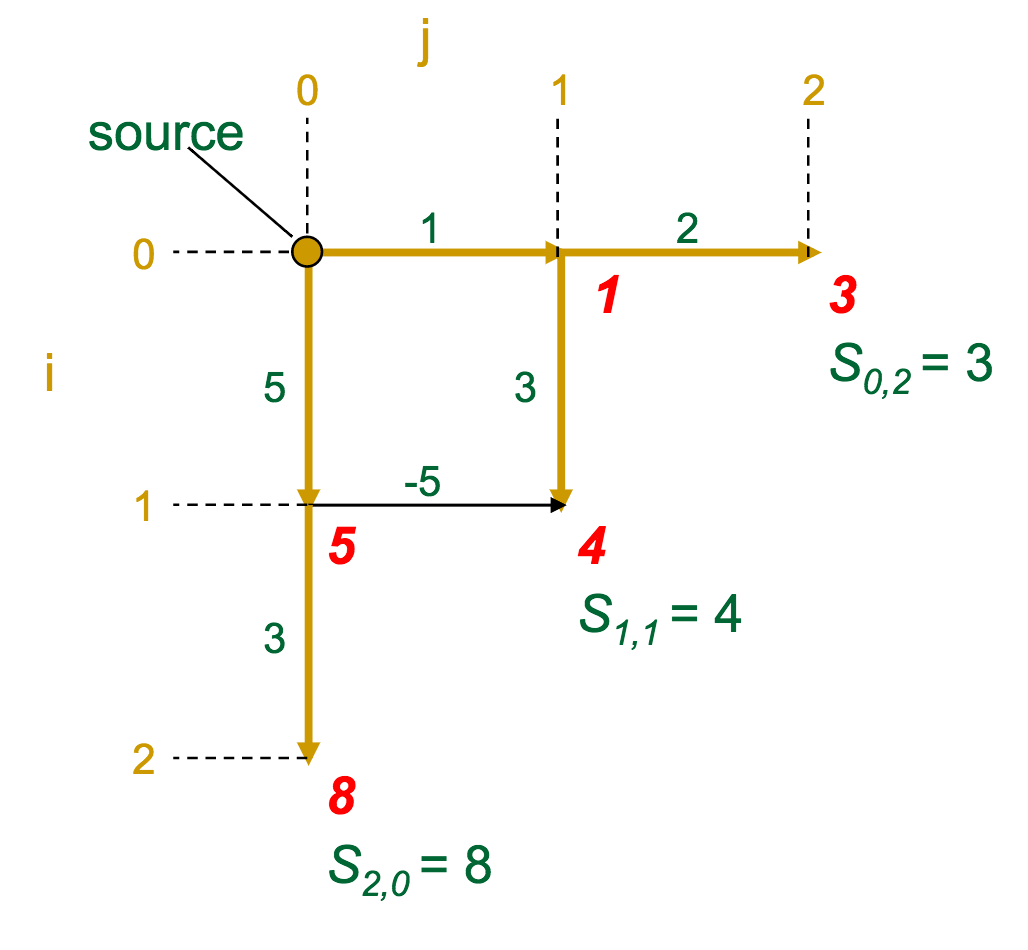

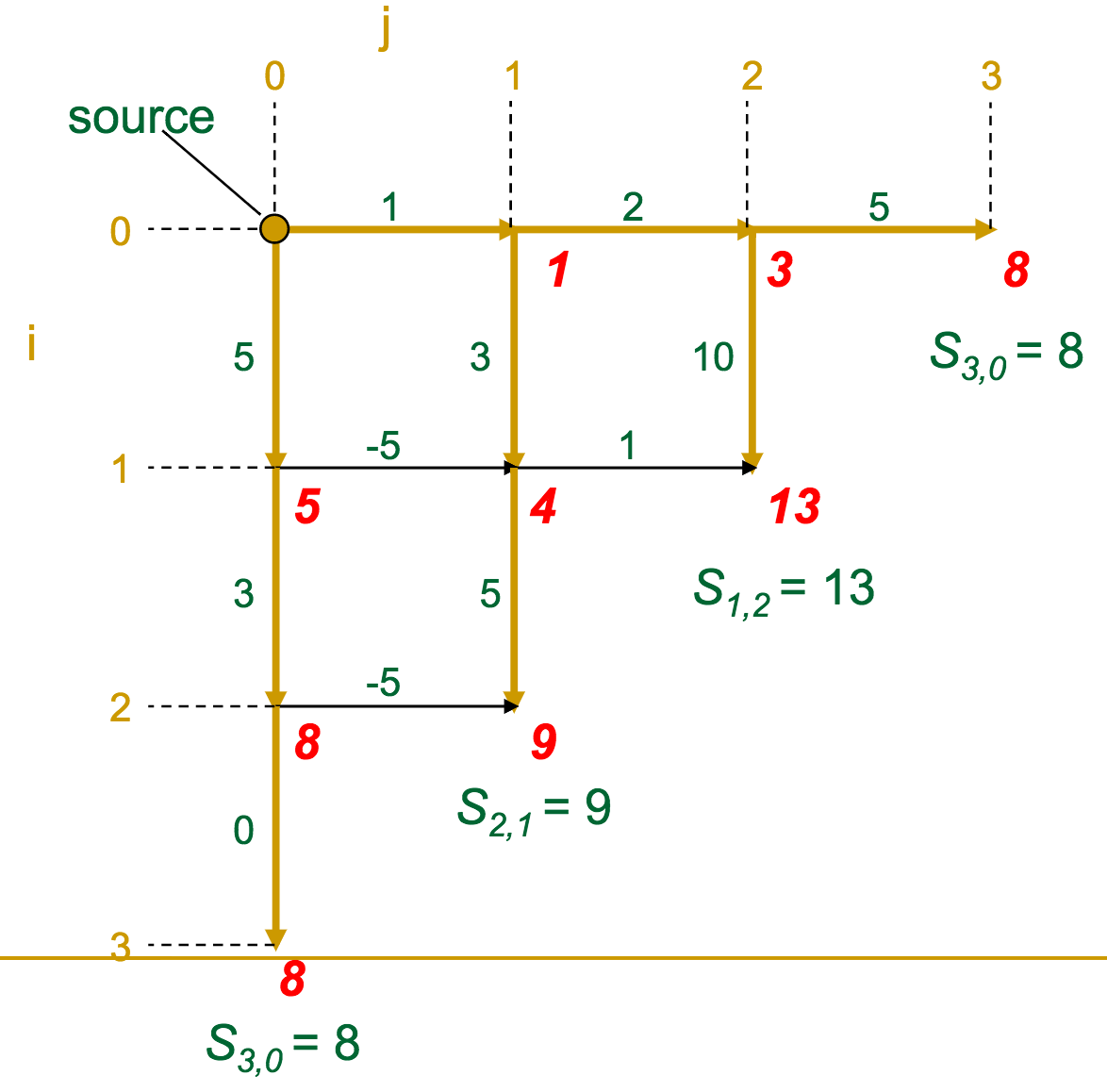

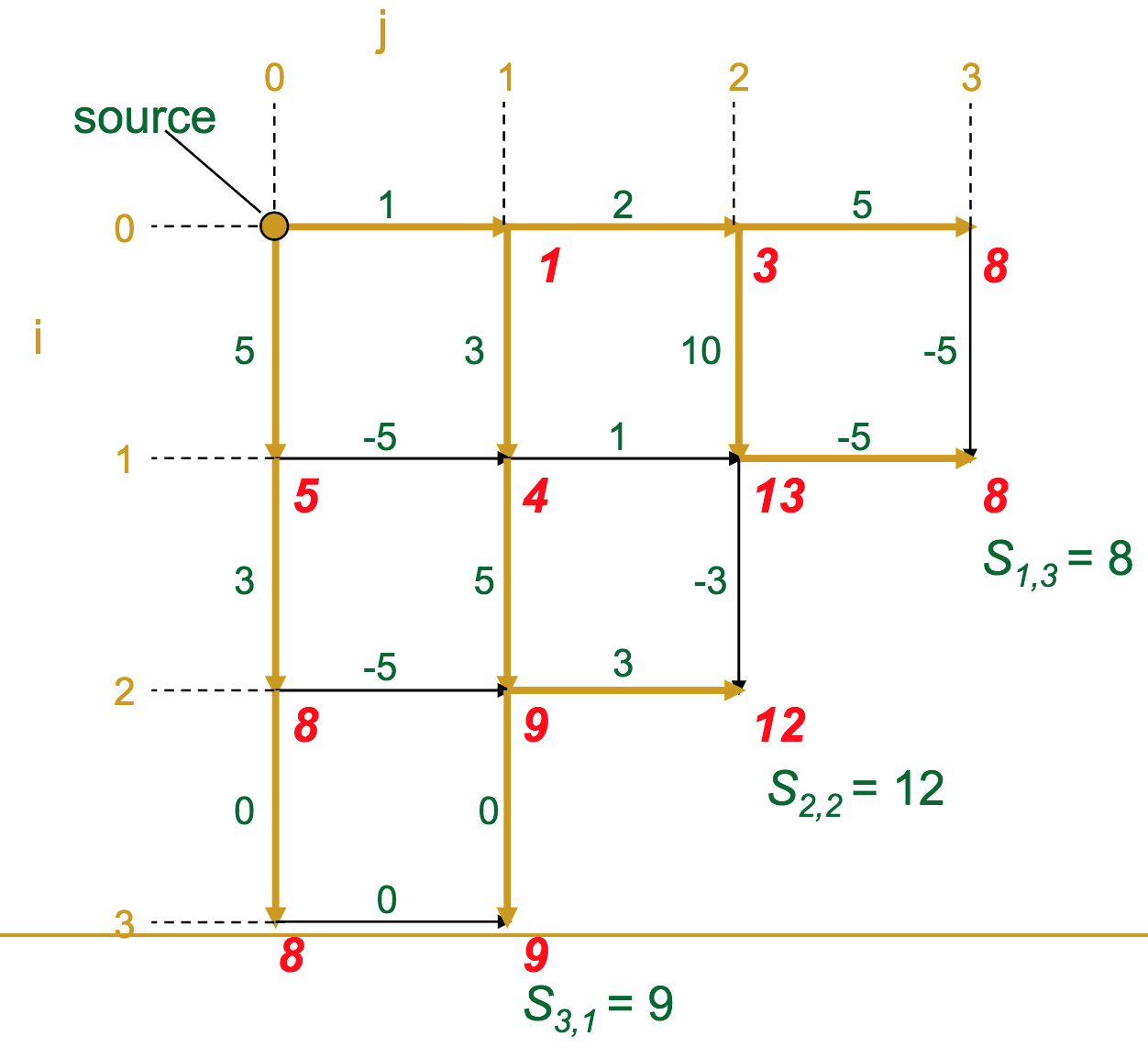

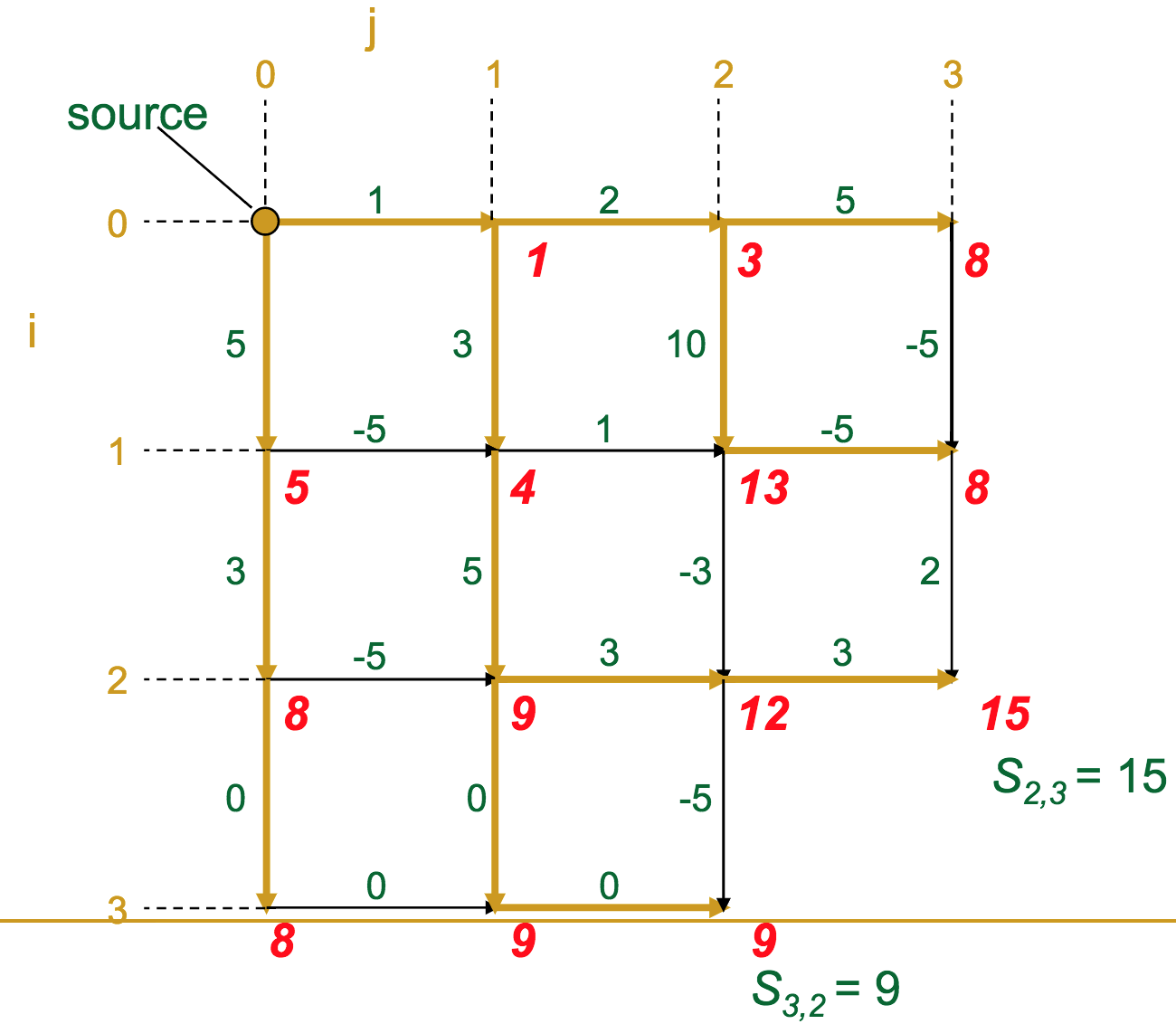

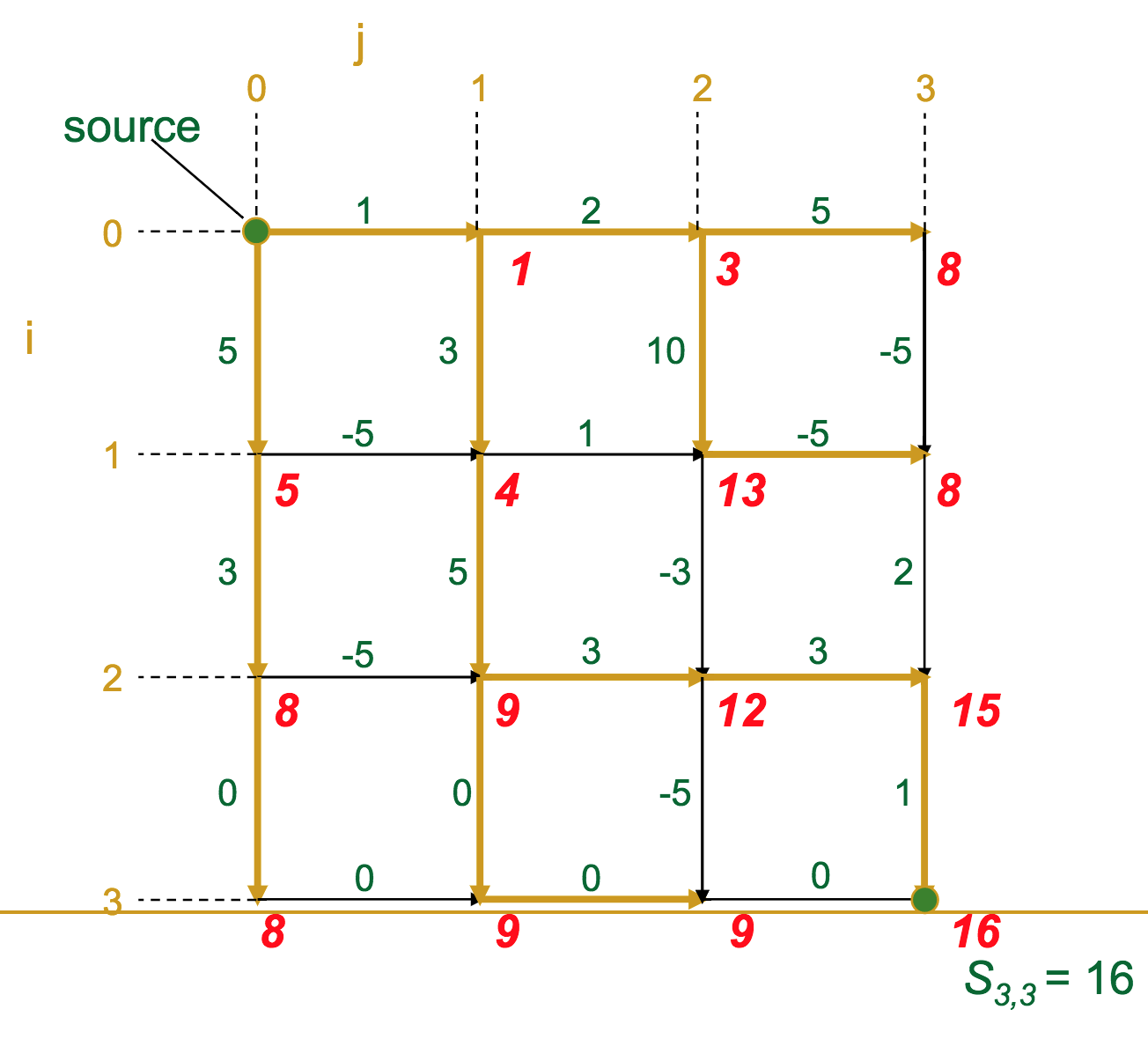

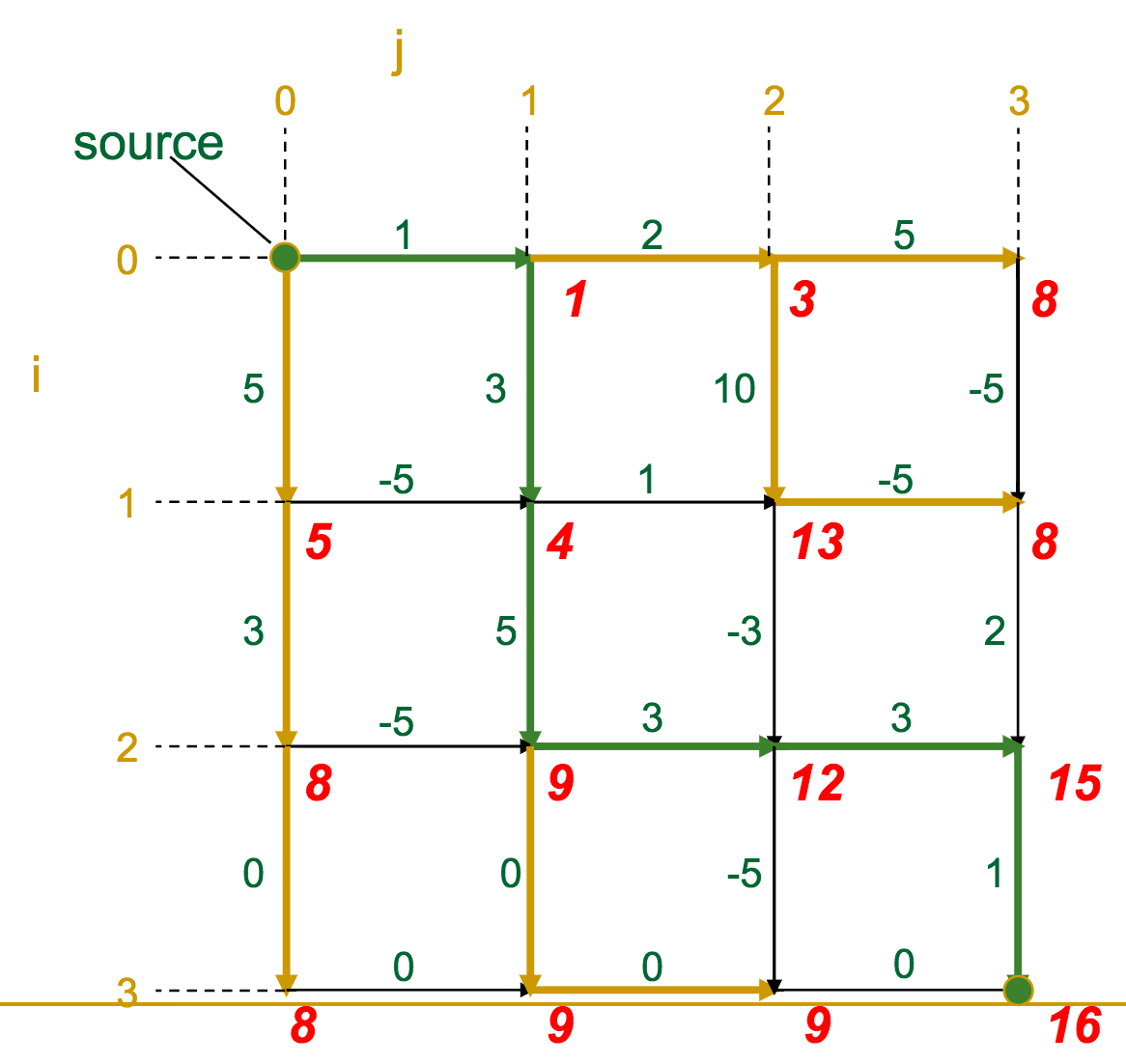

The gold edges represent those which the algorithm selects as "optimal" for each vertex.

Once we've reached the sink, it's a simple matter of backtracking along the gold edges to find the optimal route (which we highlight in green here).

Complexity¶

With the change problem, we said the runtime complexity of dynamic programming was $\mathcal{O}(Md)$, where $M$ is the amount of money, and $d$ is the number of denominations.

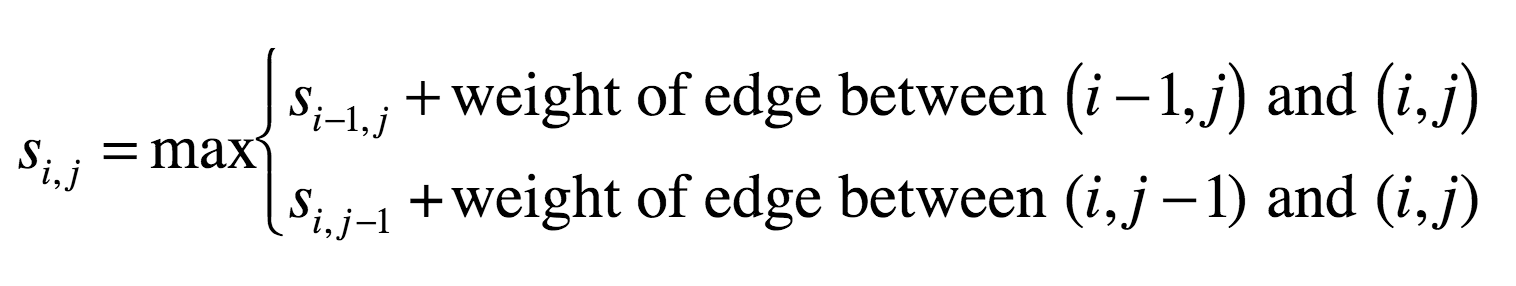

Let's make this a bit more formal. We have a graph / matrix, and each intersection $s_{i,j}$ has a score according to the recurrence:

For a matrix with $n$ rows and $m$ columns, what is the complexity?

$\mathcal{O}(nm)$. Basically, we have to look at every element of the matrix.

But that's still better than the recurrence relation we saw earlier!

Part 4: Sequence Alignment¶

So how does all this relate to sequence alignment? How does dynamic programming play into finding the longest common subsequence of two polypeptides or nucleic acid sequences?

Given two sequences, let's use dynamic programming to find their best alignment.

$v$: ATCTGATC

$w$: TGCATAC

Our nucleotide string $v$ has length 8, and $w$ has length 7. How can we align these two sequences optimally?

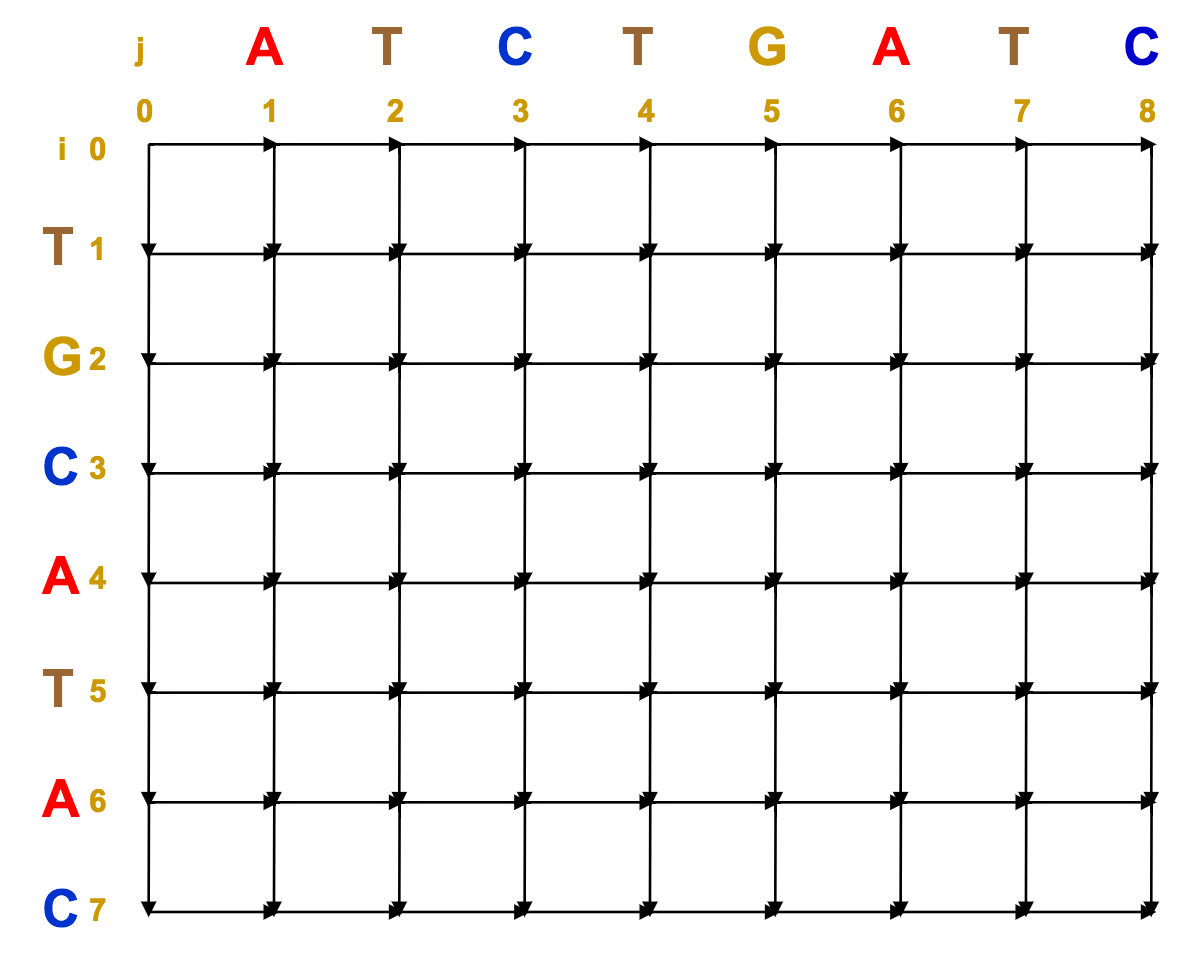

Alignment Matrix¶

We can represent these strings along the rows and columns of an alignment matrix.

Assign one sequence to the rows, and one sequence to the columns.

At each intersection / vertex, we have three options:

- Go south (insertion / deletion)

- Go east (deletion / deletion)

- Go south-east (match / mismatch)

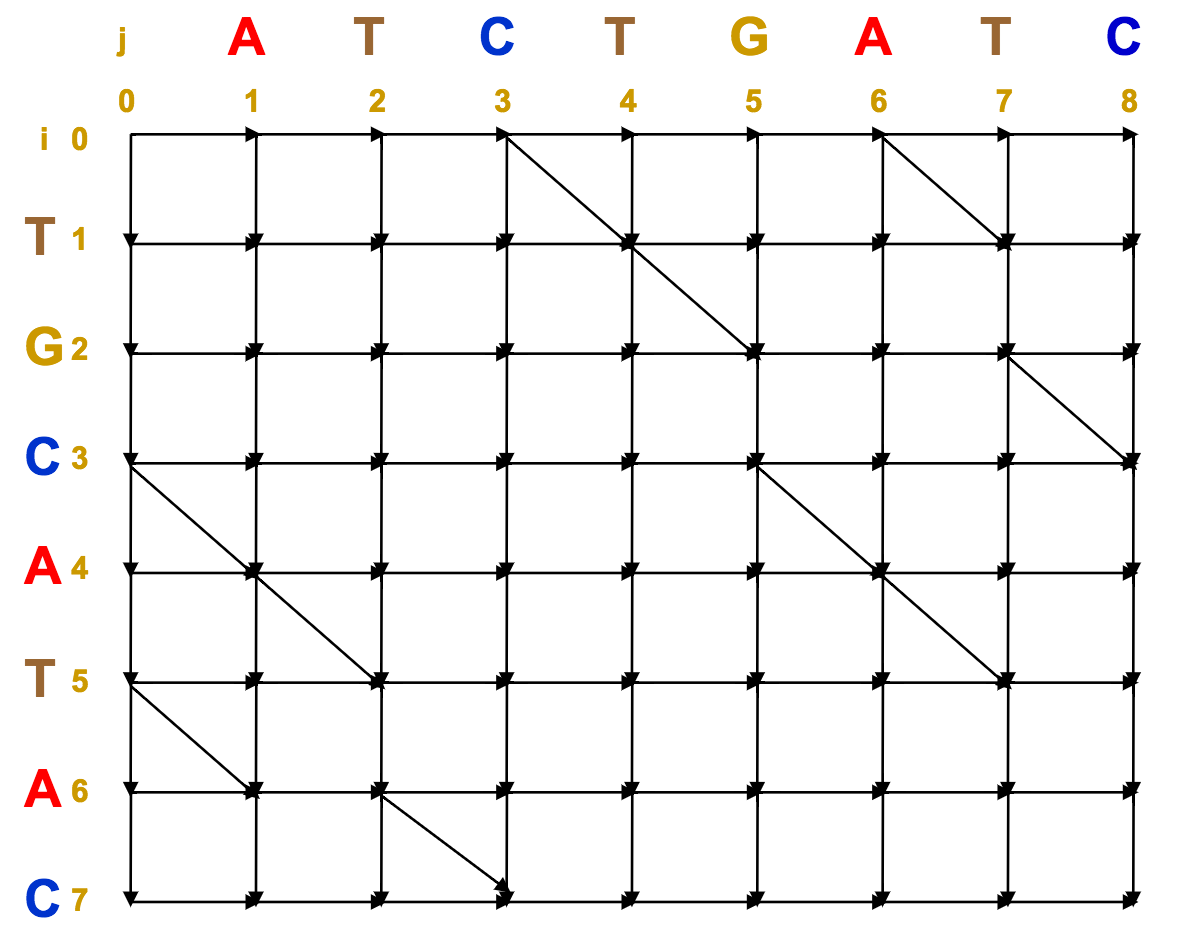

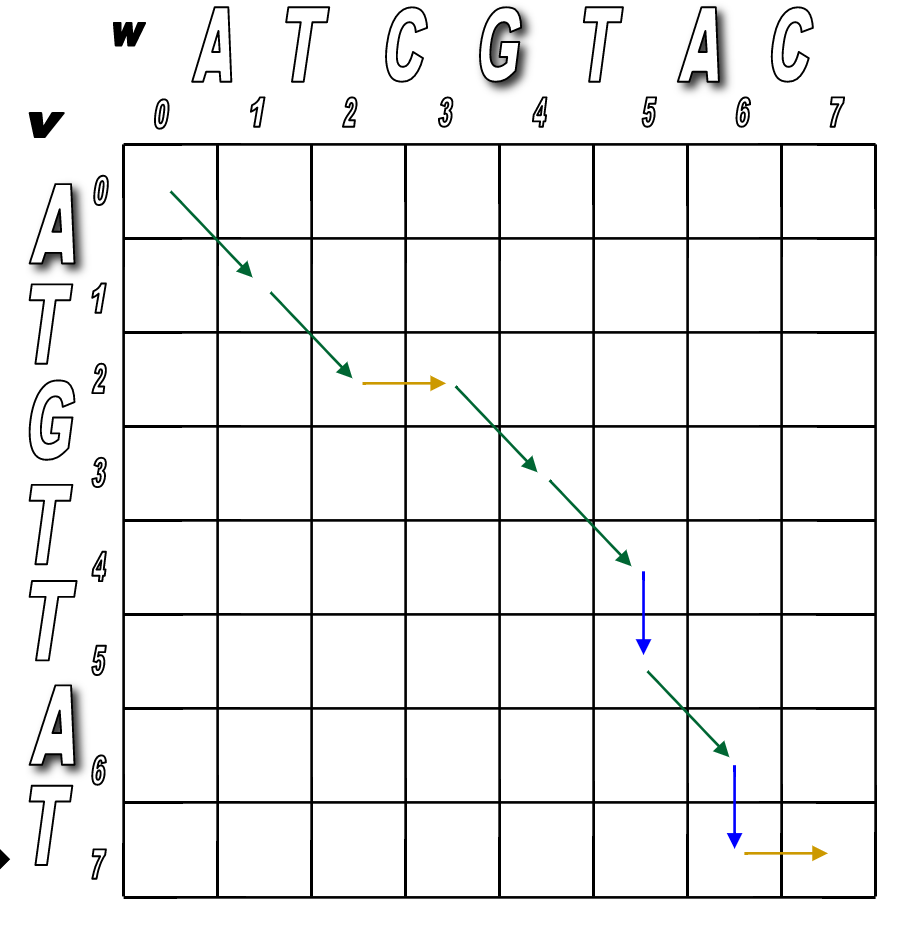

Every diagonal movement represents a match. We can immediately see all our common subsequences this way:

Now, we just need to join up as many of these aligned subsequences as possible to make the longest common subsequence, and hence, the optimal alignment.

The full path, from source (upper left) to sink (bottom right), represents a common sequence.

Using the Alignment Matrix for Edit Distance¶

- Every alignment of two sequences corresponds to a path in the alignment matrix from source to sink

- Horizontal and vertical edges correspond to indels (insertions and deletions)

- Diagonal edges correspond to matches and mismatches

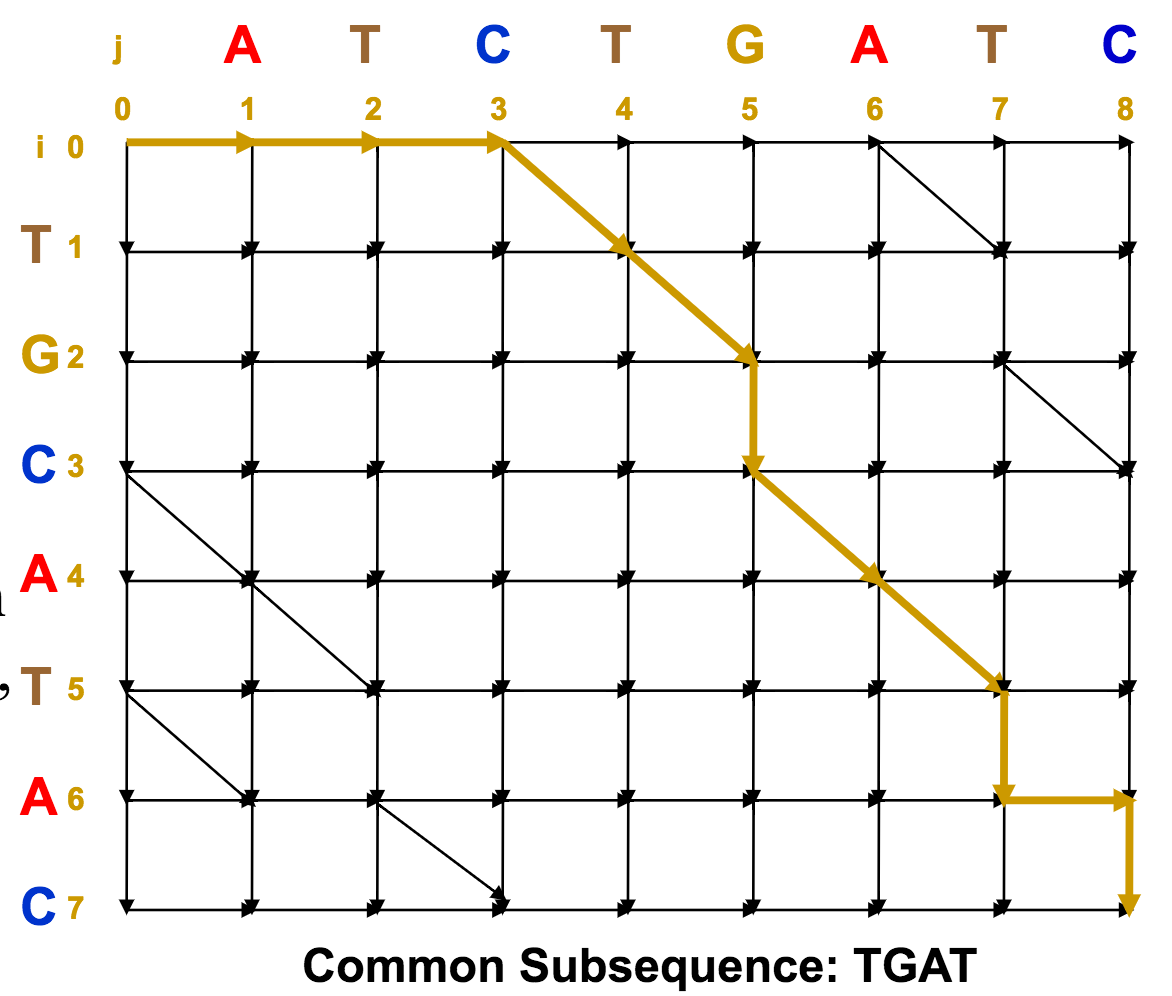

Dynamic Programming for Sequence Alignment¶

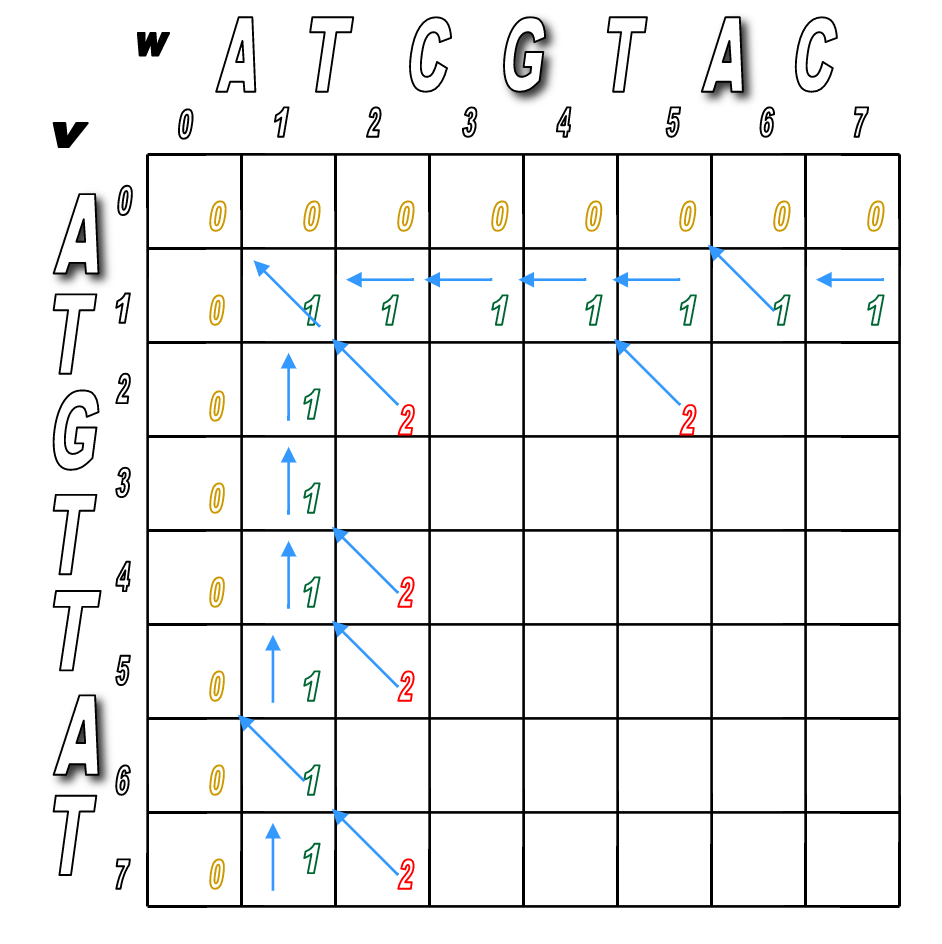

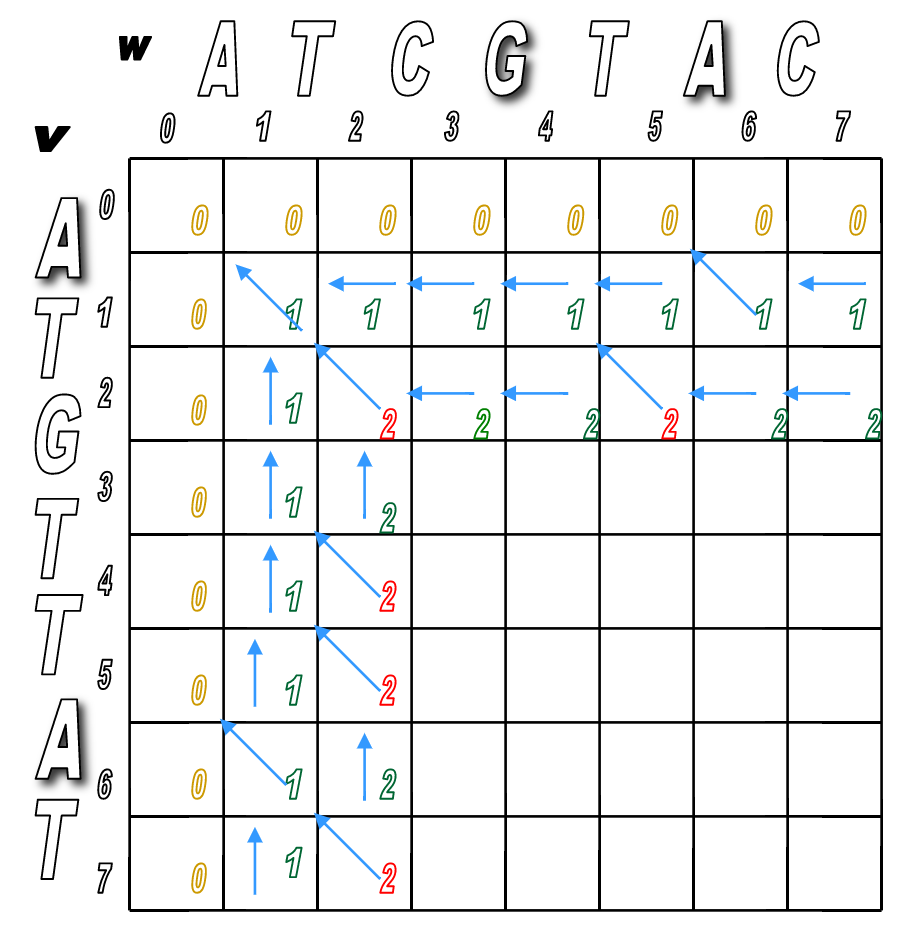

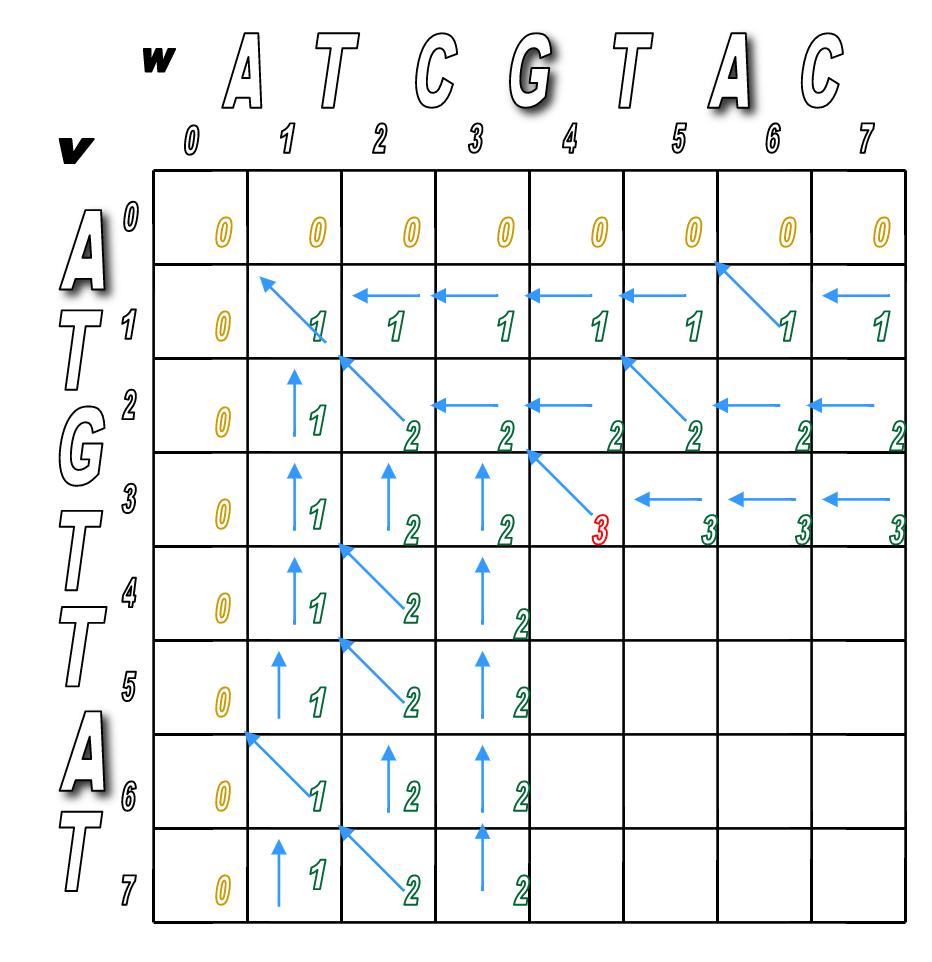

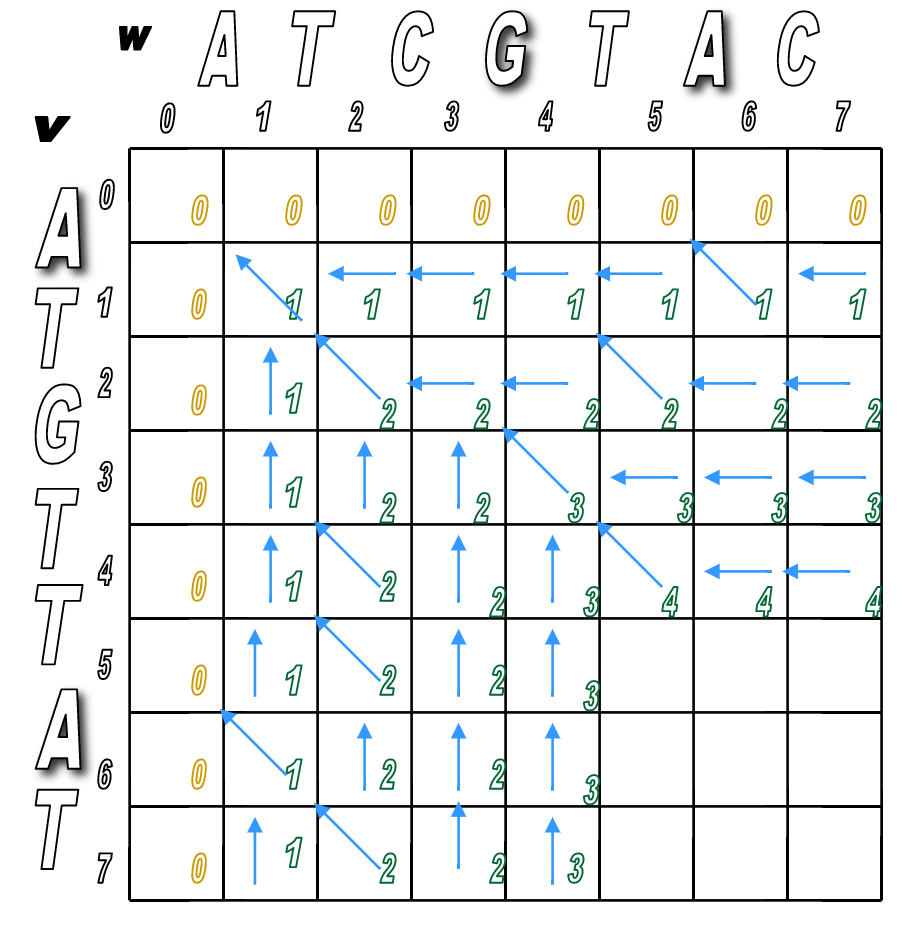

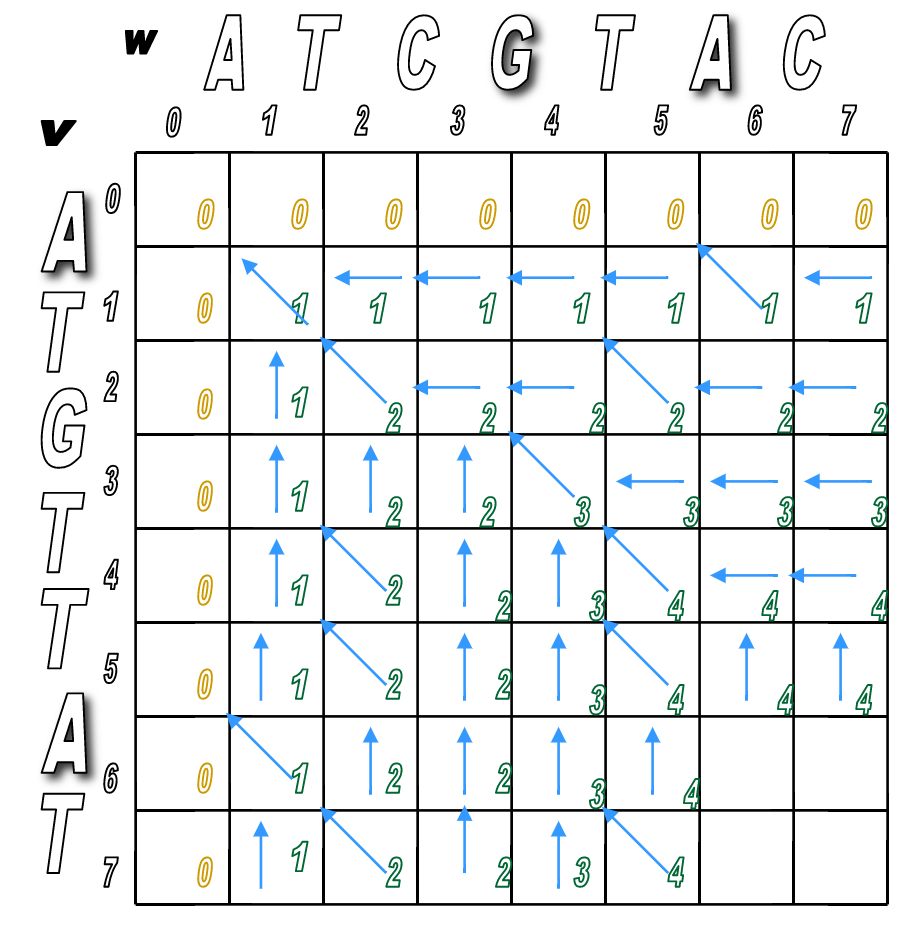

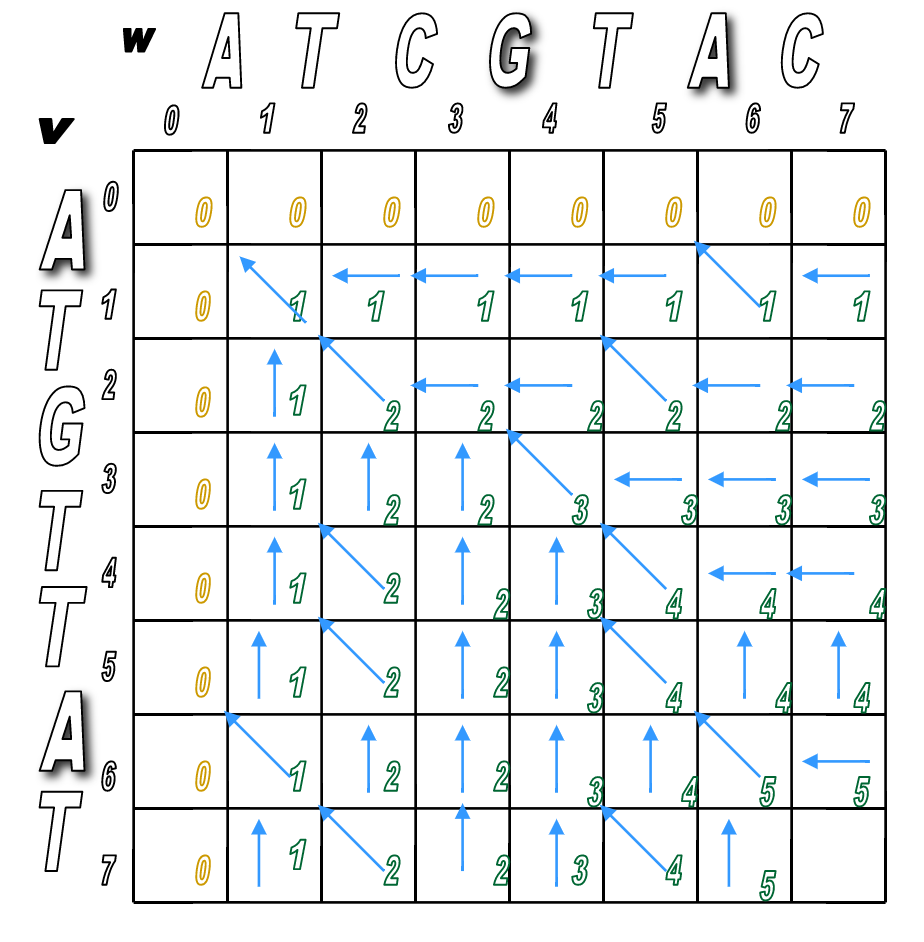

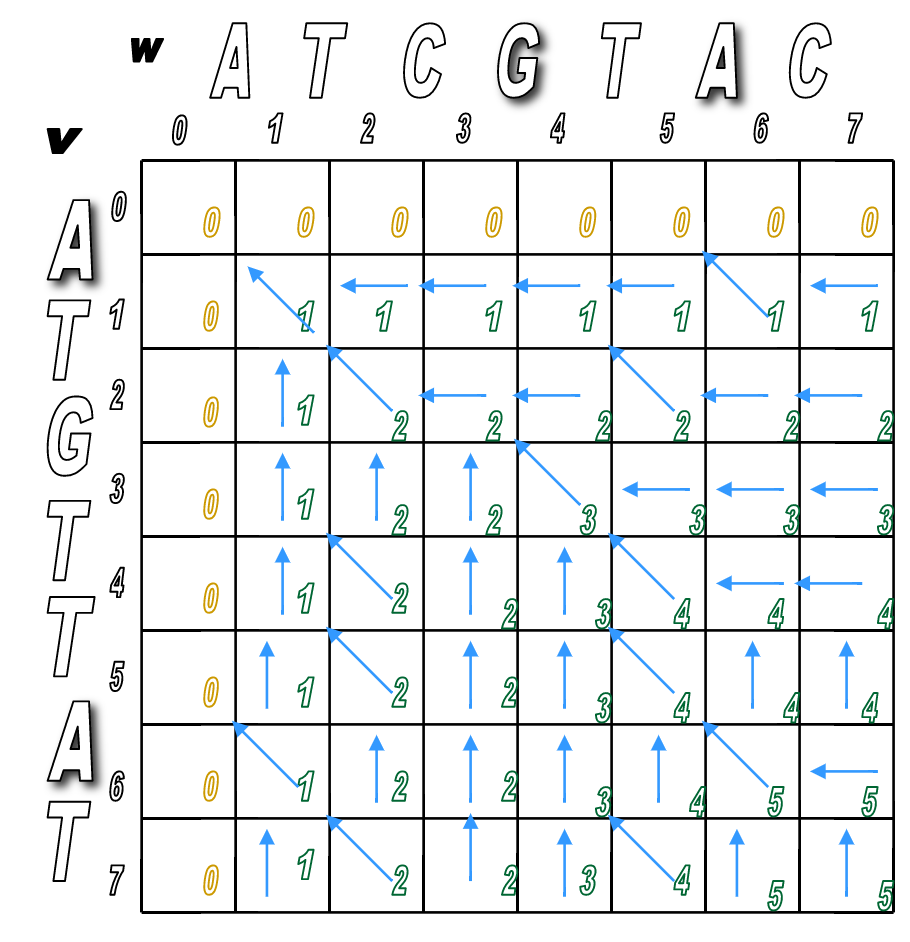

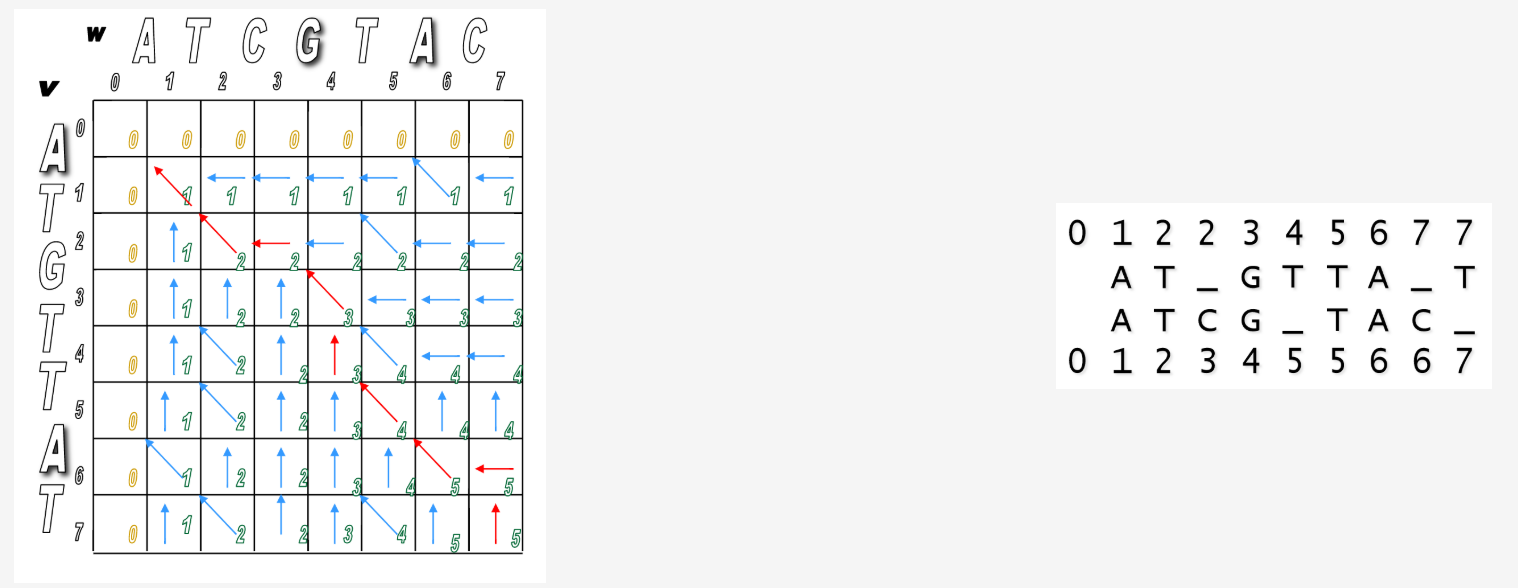

Let's see how this would play out algorithmically. Here's an example:

$v$ = ATCGTAC

$w$ = ATGTTAC

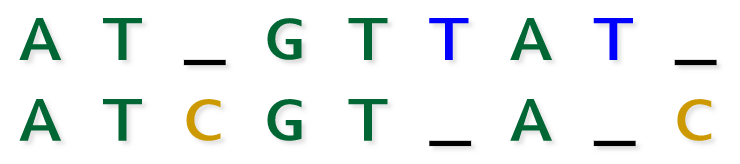

One possible alignment of the two sequences might look like this ($v$ on top, $w$ on bottom)

So the corresponding alignment matrix would have a path from source to sink like this:

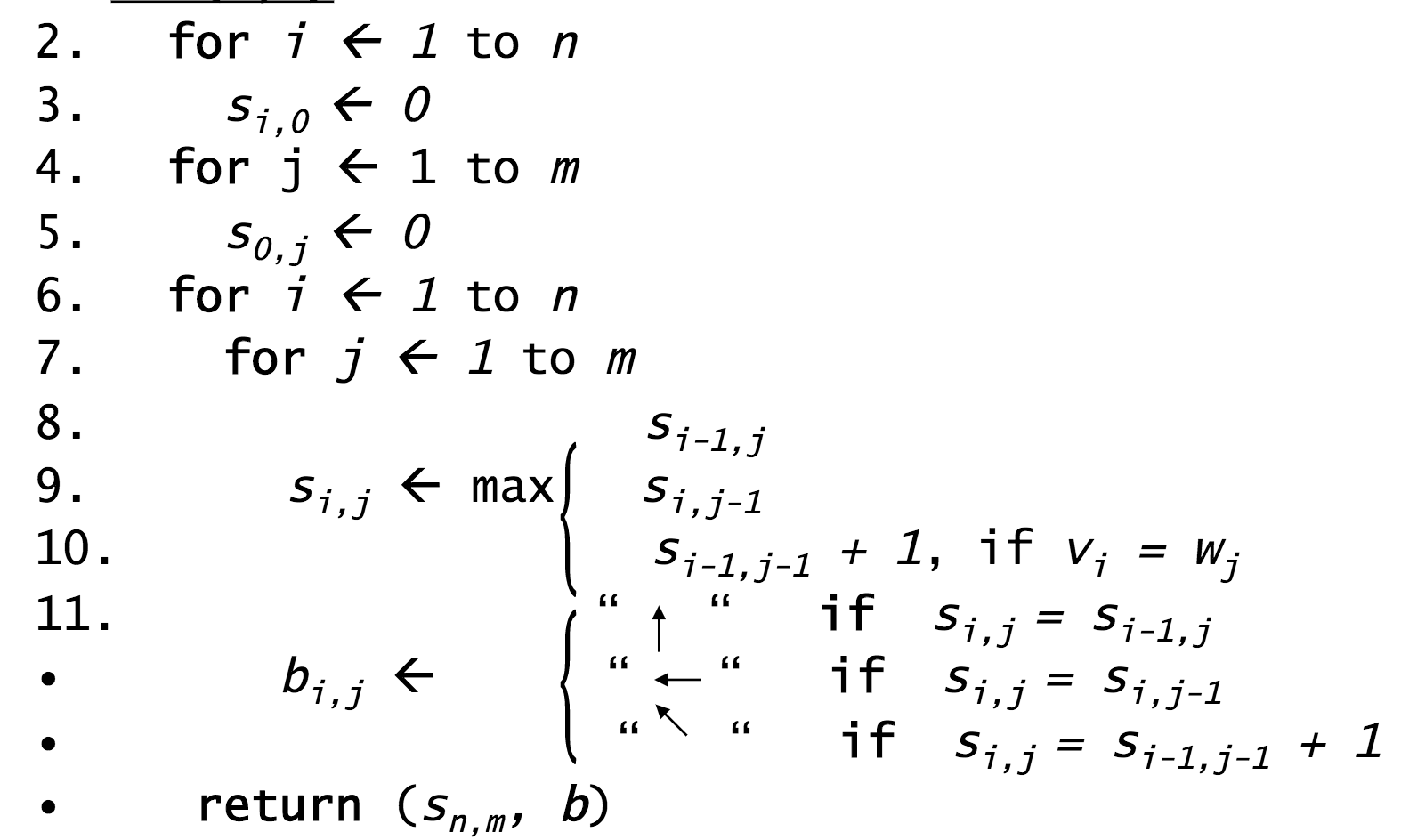

Programmatically, it would follow these steps.

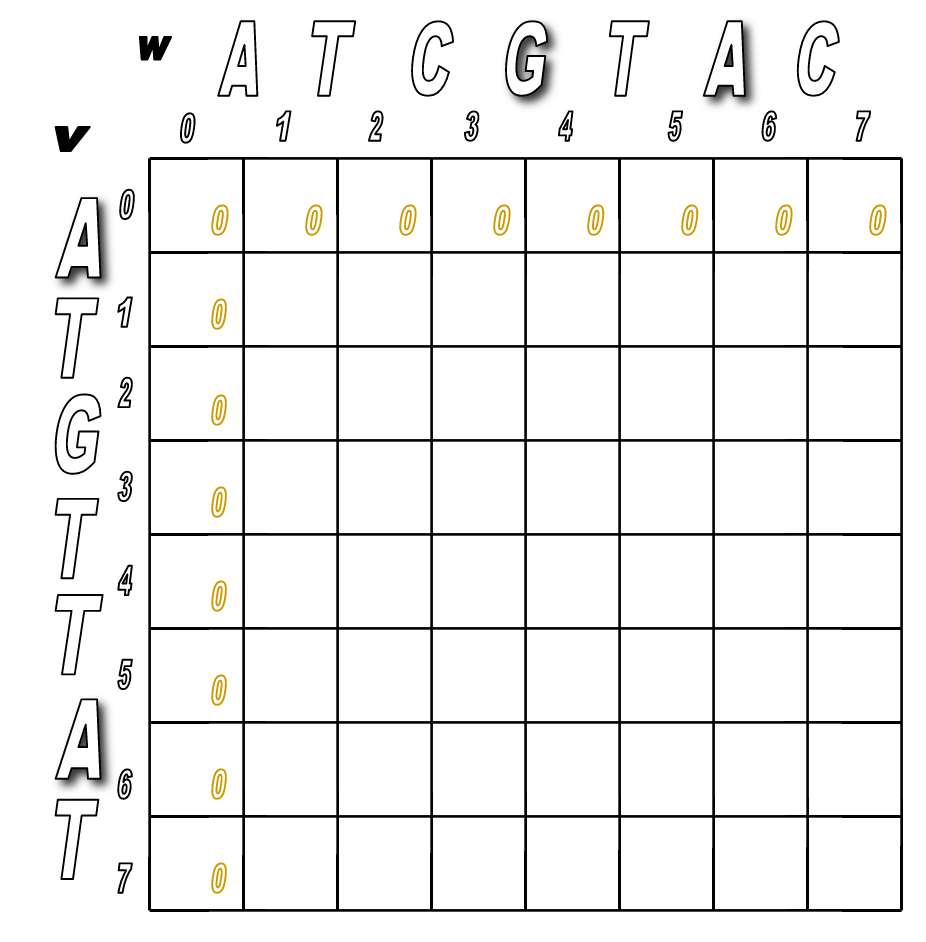

Step 1: Initialize the $0^{th}$ row and $0^{th}$ column to be all 0s.

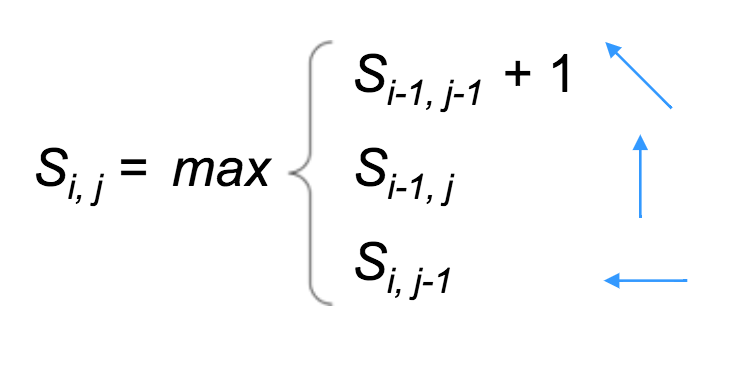

Step 2: Use the following recurrence formula to calculate $s_{i,j}$ for each $i$ and $j$ in the matrix:

- Top: a match (or mismatch)

- Middle: a deletion (with respect to $v$)

- Bottom: an insertion (with respect to $v$)

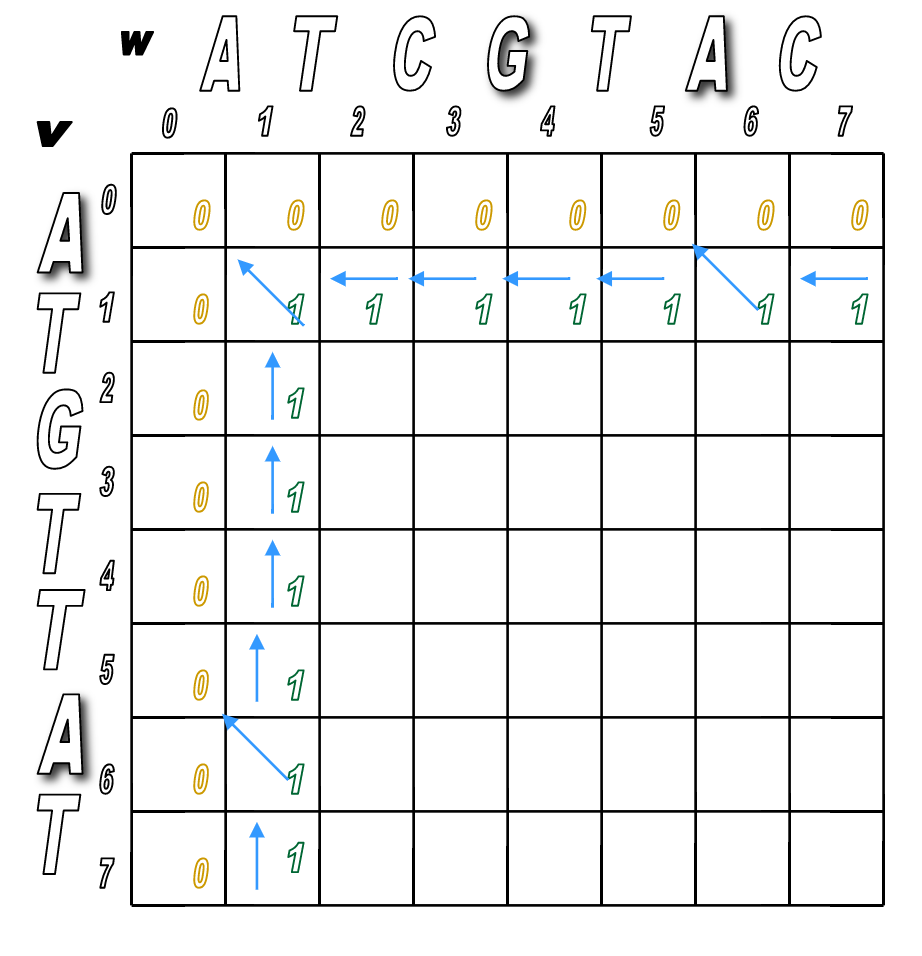

You'll pretty much run Step 2 over and over until the matrix is filled.

You'll look for any matches first (in red), then fill in the indels.

We've filled the alignment matrix! Now how do we assemble the final, optimal alignment of the two sequences?

Start at the sink and follow the arrows back!

Pseudocode¶

Some final thoughts on Dynamic Programming¶

- How could we set up this problem in Python? What would the data structures be?

- Remember edit distance? It's the measure of how different two sequences are. By contrast, the alignment score from dynamic programming is a similarity score. If edit distance is 0, what do we expect the alignment score to be?

- How could we modify the scoring procedure in dynamic programming to allow for scoring matrices like PAM and BLOSUM?

Administrivia¶

- Grades for Assignments 1 and 2 are on eLC! Ping me with questions.

- If you're struggling with the assignments, let's meet and go over these questions.

- Assignment 3 is out, and will be the last assignment before the "midterm".

- Regarding the midterm--does everyone have a laptop they could bring to class for the exam?