Lecture 2: Python Crash Course¶

CSCI 4360/6360: Data Science II

News headline the literal first day of this class in Fall 2023

Part 1: Python Background¶

Python as a language was implemented from the start by Guido van Rossum. What was originally something of a snarkily-named hobby project to pass the holidays turned into a huge open source phenomenon used by millions.

Python's history¶

The original project began in 1989.

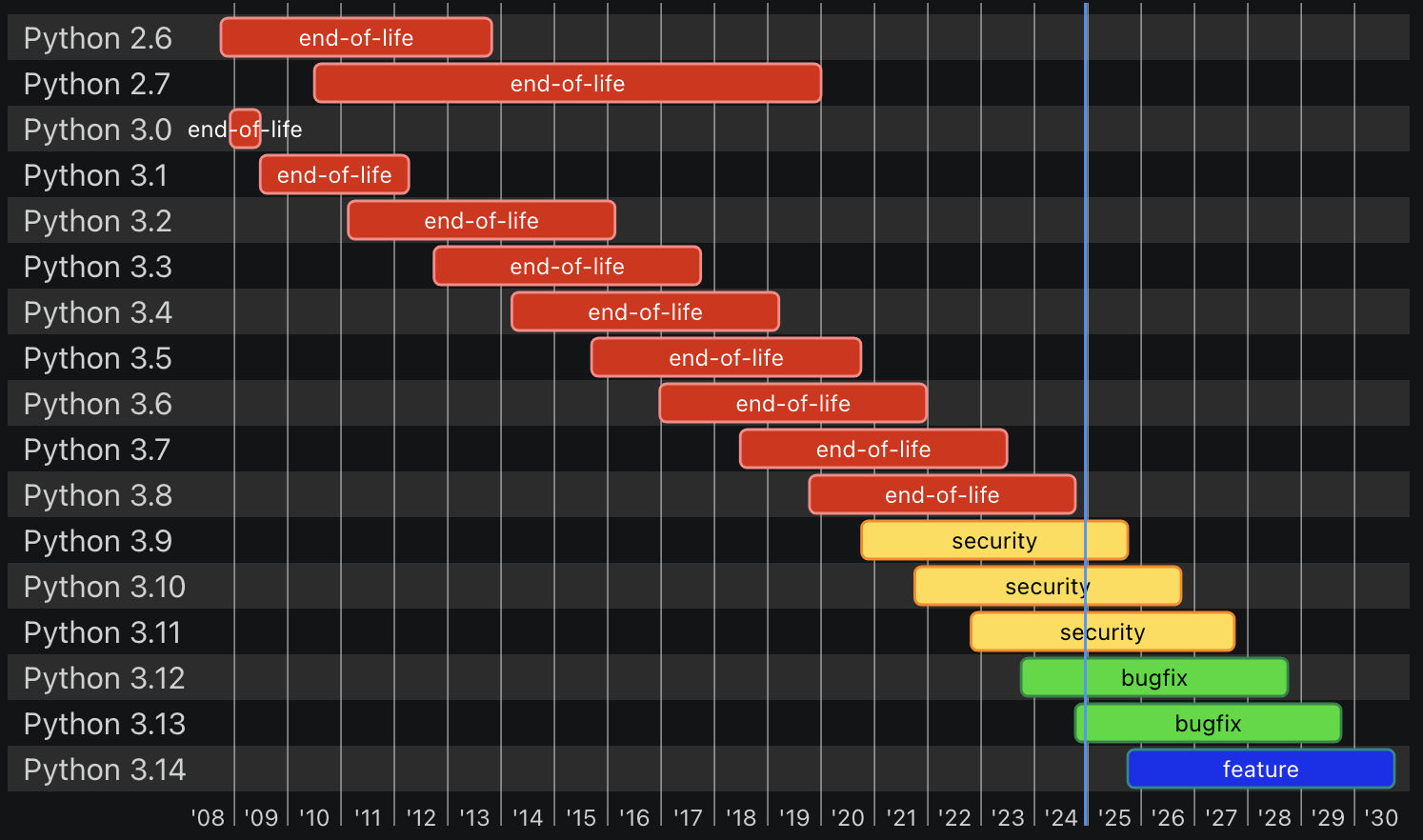

Release of Python 2.0 in 2000

Release of Python 3.0 in 2008

Python 2.0 was EOL (end-of-life) in 2020, so you should be on Python 3 now. The latest version of Python is 3.13 (though it's still a bit bleeding-edge).

You're welcome to use whatever version you want, just be aware: the AutoLab autograders will be using 3.10 - 3.11 (in general, anything 3.10 and above should be fine, though absolutely no lower than 3.9).

Python, the Language¶

Python is an intepreted language.

- Contrast with compiled languages

- Performance, ease-of-use

- Modern intertwining and blurring of compiled vs interpreted languages

Python is a very general language.

- Not designed as a specialized language for performing a specific task. Instead, it relies on third-party developers to provide these extras.

Instead, as Jake VanderPlas put it:

"Python syntax is the glue that holds your data science code together. As many scientists and statisticians have found, Python excels in that role because it is powerful, intuitive, quick to write, fun to use, and above all extremely useful in day-to-day data science tasks."

Part 2: Language Basics¶

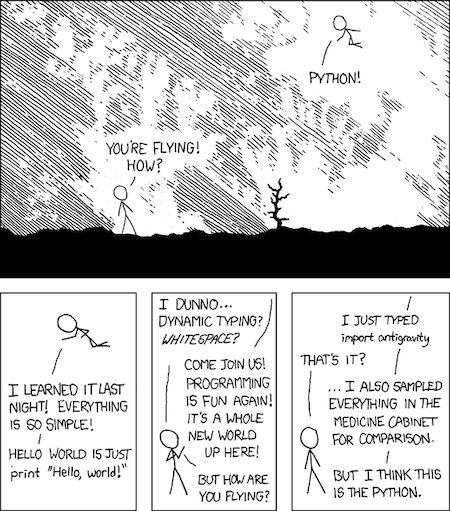

The most basic thing possible: Hello, World!

print("Hello, world!")

Hello, world!

Yep, that's all that's needed!

(Take note: the biggest different between Python 2 and 3 is the print function: it technically wasn't a function in Python 2 so much as a language construct, and so you didn't need parentheses around the string you wanted printed; in Python 3, it's a full-fledged function, and therefore requires parentheses)

Variables and Types¶

Python is dynamically-typed, meaning you don't have to declare types when you assign variables. Python is also duck-typed, a colloquialism that means it infers the best-suited variable type at runtime ("if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck...")

x = 5

type(x)

int

y = 5.5

type(y)

float

It's important to note: even though you don't have to specify a type, Python still assigns a type to variables. It would behoove you to know the types so you don't run into tricky type-related bugs!

x = 5 * 5

What's the type for x?

type(x)

int

y = 5 / 5

What's the type for y?

type(y)

float

There are functions you can use to explicitly cast a variable from one type to another:

x = 5 / 5

type(x)

float

y = int(x)

type(y)

int

z = str(y)

type(z)

str

Type Hinting¶

As of version 3.5, Python supports type hinting. The documentation makes this distinction clear:

Think of type hinting in Python as non-comment documentation.

An example directly from the typing docs:

def surface_area_of_cube(edge_length: float) -> str:

return f"The surface area of the cube is {6 * edge_length ** 2}."

The function surface_area_of_cube takes a single argument edge_length which is expected to be of type float. The function then returns a value of type str.

You can use type hinting to do type aliasing for convenience:

Vector = list[float]

# "Vector" types are now equivalent to "list[float]" types

# in the eyes of any static checkers you use

def scale(scalar: float, vector: Vector) -> Vector:

return [scalar * num for num in vector]

# passes type checking; a list of floats qualifies as a Vector.

new_vector = scale(2.0, [1.0, -4.2, 5.4])

print(new_vector)

[2.0, -8.4, 10.8]

IMPORTANT: Type hinting is a bleeding-edge feature in Python that is still undergoing a lot of changes. I struggled with this example for a good 15 minutes before realizing I was reading type hinting documentation for Python 3.13, which differs slightly from type hinting in 3.10.

Type hinting is really cool, but keep in mind: Python's runtime IGNORES type hints. They are not enforced in any way by Python; they are purely for convenience, hence why I call them "non-comment documentation."

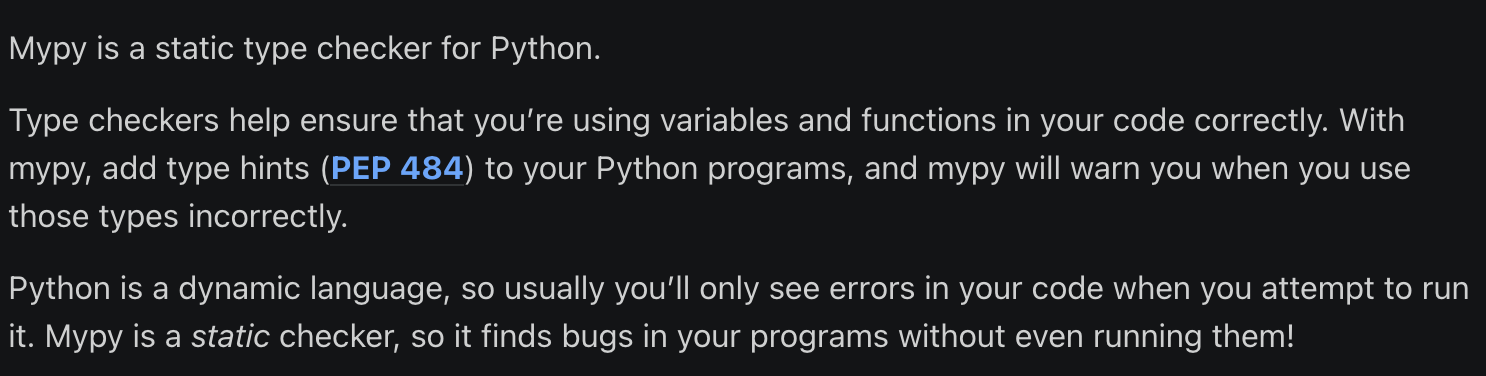

If you want to actually enforce type hints, you need a static type checker like mypy

Walrus Operator¶

Introduced in Python 3.8 (still relatively recent!), the walrus operator, or "Assignment Expression", is a way of assigning a value to a variable in mid-expression.

Other languages have had this ability for awhile, but there was heated debate about how best to implement this in Python.

Normally, you'd first assign a value to a variable, and then perform a check.

v = 10

if (v > 5):

print("We've reached this location")

We've reached this location

Alternatively, you can perform the assignment right in the middle of the expression.

if ((v := 10) > 5):

print("We've now reached this location")

We've now reached this location

Note two important changes.

- The operator itself: it's a colon ":" and an assignment "=" smashed together. They look like the walrus, hence the name.

- The assignment expression has been wrapped in an additional set of parentheses.

Just as important to note: anywhere that you could use the walrus operator, you can also break it apart into two separate expressions! This is purely for brevity, but never sacrifice clarity for it.

Data Structures¶

There are four main types of built-in Python data structures, each similar but ever-so-slightly different:

- Lists (the Python workhorse)

- Tuples

- Sets

- Dictionaries

(Note: generators and comprehensions are worthy of mention; definitely look into these as well)

Lists are basically your catch-all multi-element data structure; they can hold anything.

some_list = [1, 2, 'something', 6.2, ["another", "list!"], 7371]

print(some_list[3])

type(some_list)

6.2

list

Tuples are like lists, except they're immutable once you've built them (and denoted by parentheses, instead of brackets).

some_tuple = (1, 2, 'something', 6.2, ["another", "list!"], 7371)

print(some_tuple[5])

type(some_tuple)

7371

tuple

Sets are probably the most different: they are mutable (can be changed), but are unordered and can only contain unique items (they automatically drop duplicates you try to add). They are denoted by braces.

some_set = {1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 86, "something", 73}

some_set.add(1)

print(some_set)

type(some_set)

{73, 'something', 1, 86}

set

Finally, dictionaries. Other terms that may be more familiar include: maps, hashmaps, or associative arrays. They're a combination of sets (for their key mechanism) and lists (for their value mechanism).

some_dict = {"key": "value", "another_key": [1, 3, 4], 3: ["this", "value"]}

print(some_dict["another_key"])

type(some_dict)

[1, 3, 4]

dict

Dictionaries explicitly set up a mapping between a key--keys are unique and unordered, exactly like sets--to values, which are an arbitrary list of items. These are very powerful structures for data science-y applications.

Slicing and Indexing¶

Ordered data structures in Python are 0-indexed (like C, C++, and Java). This means the first elements are at index 0:

print(some_list)

[1, 2, 'something', 6.2, ['another', 'list!'], 7371]

index = 0

print(some_list[index])

1

However, using colon notation, you can "slice out" entire sections of ordered structures.

start = 0

end = 3

print(some_list[start : end])

[1, 2, 'something']

Note that the starting index is inclusive, but the ending index is exclusive. Also, if you omit the starting index, Python assumes you mean 0 (start at the beginning); likewise, if you omit the ending index, Python assumes you mean "go to the very end".

print(some_list[:end])

[1, 2, 'something']

start = 1

print(some_list[start:])

[2, 'something', 6.2, ['another', 'list!'], 7371]

Loops¶

Python supports two kinds of loops: for and while

for loops in Python are, in practice, closer to for each loops in other languages: they iterate through collections of items, rather than incrementing indices.

for item in some_list:

print(item)

1 2 something 6.2 ['another', 'list!'] 7371

- the collection to be iterated through is at the end (

some_list) - the current item being iterated over is given a variable after the

forstatement (item) - the loop body says what to do in an iteration (

print(item))

But if you need to iterate by index, check out the enumerate function:

for index, item in enumerate(some_list):

print("{}: {}".format(index, item))

0: 1 1: 2 2: something 3: 6.2 4: ['another', 'list!'] 5: 7371

while loops operate as you've probably come to expect: there is some associated boolean condition, and as long as that condition remains True, the loop will keep happening.

i = 0

while i < 10:

print(i)

i += 2

0 2 4 6 8

IMPORTANT: Do not forget to perform the update step in the body of the while loop! After using for loops, it's easy to become complacent and think that Python will update things automatically for you. If you forget that critical i += 2 line in the loop body, this loop will go on forever...

Another cool looping utility when you have multiple collections of identical length you want to loop through simultaneously: the zip() function

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list2 = [4, 5, 6]

list3 = [7, 8, 9]

for x, y, z in zip(list1, list2, list3):

print("{} {} {}".format(x, y, z))

1 4 7 2 5 8 3 6 9

This "zips" together the lists and picks corresponding elements from each for every loop iteration. Way easier than trying to set up a numerical index to loop through all three simultaneously, but you can even combine this with enumerate to do exactly that:

for index, (x, y, z) in enumerate(zip(list1, list2, list3)):

print("{}: ({}, {}, {})".format(index, x, y, z))

0: (1, 4, 7) 1: (2, 5, 8) 2: (3, 6, 9)

Conditionals¶

Conditionals, or if statements, allow you to branch the execution of your code depending on certain circumstances.

In Python, this entails three keywords: if, elif, and else.

grade = 82

if grade > 90:

print("A")

elif grade > 80:

print("B")

else:

print("Something else")

B

A couple important differences from C/C++/Java parlance:

- NO parentheses around the boolean condition!

- It's not "

else if" or "elseif", just "elif". It's admittedly weird, but it's Python

Conditionals, when used with loops, offer a powerful way of slightly tweaking loop behavior with two keywords: continue and break.

The former is used when you want to skip an iteration of the loop, but nonetheless keep going on to the next iteration.

list_of_data = [4.4, 1.2, 6898.32, "bad data!", 5289.24, 25.1, "other bad data!", 52.4]

for x in list_of_data:

if type(x) == str:

continue

# This stuff gets skipped anytime the "continue" is run

print(x)

4.4 1.2 6898.32 5289.24 25.1 52.4

break, on the other hand, literally slams the brakes on a loop, pulling you out one level of indentation immediately.

import random

i = 0

iters = 0

while True:

iters += 1

i += random.randint(0, 10)

if i > 1000:

break

print(iters)

200

def http_error(status):

match status:

case 400:

return "Bad request"

case 404:

return "Not found"

case 418:

return "I'm a teapot"

# If an exact match is not confirmed, this last case will be used if provided

case _:

return "Something's wrong with the internet"

http_error(404)

'Not found'

http_error(502)

"Something's wrong with the internet"

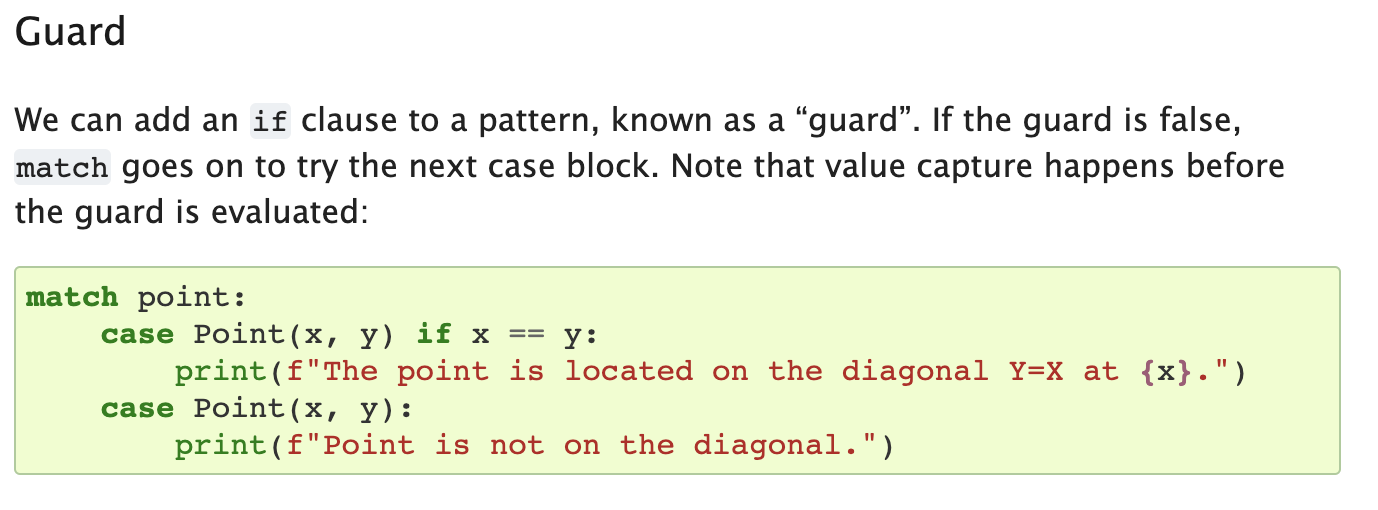

These can get really complex, so I'd recommend checking out the PEP documentation.

File I/O¶

Python has a great file I/O library. There are usually third-party libraries that expedite reading certain often-used formats (JSON, XML, binary formats, etc), but you should still be familiar with input/output handles and how they work:

text_to_write = "I want to save this to a file."

f = open("some_file.txt", "w")

f.write(text_to_write)

f.close()

This code writes the string on the first line to a file named some_file.txt. We can read it back:

f = open("some_file.txt", "r")

from_file = f.read()

f.close()

print(from_file)

I want to save this to a file.

Take note what changed: when writing, we used a "w" character in the open argument, but when reading we used "r". Hopefully this is easy to remember.

Also, when reading/writing binary files, you have to include a "b": "rb" or "wb".

Functions¶

A core tenet in writing functions is that functions should do one thing, and do it well.

Writing good functions makes code much easier to troubleshoot and debug, as the code is already logically separated into components that perform very specific tasks. Thus, if your application is breaking, you usually have a good idea where to start looking.

WARNING: It's very easy to get caught up writing "god functions": one or two massive functions that essentially do everything you need your program to do. But if something breaks, this design is very difficult to debug.

Homework assignments will often require you to break your code into functions so different portions can be autograded.

Functions have a header definition and a body:

def some_function(): # This line is the header

pass # Everything after (that's indented) is the body

This function doesn't do anything, but it's perfectly valid. We can call it:

some_function()

Not terribly interesting, but a good outline. To make it interesting, we should add input arguments and return values:

def vector_magnitude(vector):

d = 0.0

for x in vector:

d += x ** 2

return d ** 0.5

v1 = [1, 1]

d1 = vector_magnitude(v1)

print(d1)

1.4142135623730951

v2 = [53.3, 13.4]

d2 = vector_magnitude(v2)

print(d2)

54.95862079783298

NumPy Arrays¶

If you looked at our previous vector_magnitude function and thought "there must be an easier way to do this", then you were correct: that easier way is NumPy arrays.

NumPy arrays are the result of taking Python lists and adding a ton of back-end C++ code to make them really efficient.

Two areas where they excel: vectorized programming and fancy indexing.

Vectorized programming is perfectly demonstrated with our previous vector_magnitude function: since we're performing the same operation on every element of the vector, NumPy allows us to build code that implicitly handles the loop

import numpy as np

def vectorized_magnitude(vector):

return (vector ** 2).sum() ** 0.5

v1 = np.array([1, 1])

d1 = vectorized_magnitude(v1)

print(d1)

1.4142135623730951

v2 = np.array([53.3, 13.4])

d2 = vectorized_magnitude(v2)

print(d2)

54.95862079783298

We've also seen indexing and slicing before; here, however, NumPy really shines.

Let's say we have some super high-dimensional data:

X = np.random.random((500, 600, 250))

We can take statistics of any dimension or slice we want:

X[:400, 100:200, 0].mean()

0.49956684956905956

X[X < 0.01].std()

0.0028872417363789192

X[:400, 100:200, 0].mean(axis = 1)

array([0.49944172, 0.47224418, 0.517016 , 0.50349409, 0.46108838,

0.48671116, 0.44074704, 0.57138506, 0.46698106, 0.47233007,

0.50659231, 0.52285567, 0.48836735, 0.5033266 , 0.51291024,

0.49224532, 0.50181827, 0.51582447, 0.5169269 , 0.45603042,

0.49091331, 0.48080555, 0.45988305, 0.47888684, 0.47576944,

0.49183819, 0.49314842, 0.49403733, 0.46064221, 0.4553653 ,

0.47834965, 0.49981028, 0.50150973, 0.49048384, 0.43660323,

0.5182332 , 0.5299335 , 0.53405866, 0.50739176, 0.47930836,

0.51570378, 0.46031199, 0.47148859, 0.51785771, 0.50412137,

0.42598752, 0.47060743, 0.51522468, 0.49033351, 0.52644648,

0.51289712, 0.49268783, 0.47309393, 0.50397807, 0.50025523,

0.5109229 , 0.49934955, 0.49763461, 0.49749783, 0.52540606,

0.51153779, 0.5483544 , 0.47759441, 0.51782639, 0.53851302,

0.50614338, 0.44742773, 0.50187189, 0.52683583, 0.53371706,

0.49960892, 0.52164817, 0.5004231 , 0.51978887, 0.55740953,

0.47009899, 0.5374541 , 0.55775634, 0.49384248, 0.46166015,

0.45705687, 0.50032478, 0.48580515, 0.52434765, 0.46575697,

0.5048663 , 0.50845653, 0.48783786, 0.45561966, 0.50996148,

0.44267819, 0.46429146, 0.49080507, 0.56099999, 0.51118655,

0.51626106, 0.46647207, 0.5022075 , 0.53726753, 0.5273155 ,

0.48250798, 0.44602433, 0.54594293, 0.44886197, 0.52085765,

0.5172152 , 0.510806 , 0.53143531, 0.49686568, 0.54907925,

0.47103954, 0.4569552 , 0.50612796, 0.47359769, 0.46726589,

0.49092668, 0.52160274, 0.49445655, 0.47481545, 0.51986045,

0.4645771 , 0.50504025, 0.48598514, 0.54349689, 0.52886988,

0.48951703, 0.49874588, 0.51261301, 0.51174858, 0.44672477,

0.50939732, 0.49926906, 0.52995372, 0.49915156, 0.48606955,

0.45879912, 0.4993576 , 0.47732875, 0.51422616, 0.50842305,

0.52606065, 0.51056631, 0.52692134, 0.51360492, 0.43115107,

0.50508275, 0.51537996, 0.51384165, 0.49523427, 0.51522605,

0.52643971, 0.54313007, 0.50402494, 0.54279303, 0.53794727,

0.47662113, 0.55428043, 0.50103287, 0.45111527, 0.51048139,

0.50092177, 0.47751149, 0.49007899, 0.46597269, 0.49654727,

0.60071381, 0.47776453, 0.51690874, 0.51121973, 0.50009558,

0.49712861, 0.49690188, 0.5171476 , 0.53716952, 0.46234302,

0.45343986, 0.55212739, 0.49821131, 0.47929445, 0.49196264,

0.48724377, 0.5151308 , 0.51013592, 0.55465297, 0.51634832,

0.47694583, 0.47757639, 0.50539882, 0.50556321, 0.56490288,

0.47782577, 0.46904687, 0.5017327 , 0.49909327, 0.48725312,

0.48349753, 0.47363641, 0.55014743, 0.47928807, 0.45933692,

0.4917468 , 0.51841705, 0.50122563, 0.49939172, 0.53694635,

0.5066837 , 0.46457108, 0.49269088, 0.44310722, 0.48491748,

0.50766502, 0.48549954, 0.53271156, 0.46237328, 0.53034208,

0.49791838, 0.53811023, 0.54690621, 0.49264095, 0.44635657,

0.50149166, 0.51886277, 0.50646291, 0.54953599, 0.49604619,

0.49063266, 0.48878558, 0.47588801, 0.50168612, 0.47615474,

0.52167071, 0.45285666, 0.49851434, 0.4457162 , 0.48632062,

0.46622351, 0.51003479, 0.51390749, 0.50246842, 0.48775464,

0.48737728, 0.47531672, 0.47118079, 0.54723681, 0.51643477,

0.4850125 , 0.5449987 , 0.47502235, 0.47689017, 0.5564529 ,

0.53008977, 0.56001498, 0.49498323, 0.51349286, 0.50050063,

0.5168905 , 0.51821422, 0.46100034, 0.48183402, 0.49043079,

0.50220385, 0.50896885, 0.49612849, 0.4972982 , 0.48411812,

0.47877529, 0.52273271, 0.50690892, 0.49702295, 0.51170299,

0.48419898, 0.55120715, 0.48788084, 0.49368935, 0.47958947,

0.51375701, 0.55321104, 0.48817874, 0.5601759 , 0.50582612,

0.46503825, 0.4935711 , 0.51537612, 0.47421267, 0.46078434,

0.54146113, 0.48016893, 0.57660981, 0.45924089, 0.52338895,

0.54414314, 0.4924024 , 0.49816681, 0.50176946, 0.49535534,

0.51569646, 0.49201297, 0.47665844, 0.55592794, 0.51593156,

0.46550959, 0.4901271 , 0.46782311, 0.53322462, 0.51293972,

0.50623515, 0.50206964, 0.51018483, 0.47214767, 0.4875291 ,

0.52322358, 0.50890249, 0.49742876, 0.48866275, 0.49913119,

0.50038124, 0.50405758, 0.50284793, 0.53134594, 0.49120772,

0.47119844, 0.47984838, 0.46896369, 0.5162869 , 0.51060861,

0.46716994, 0.46138321, 0.51831758, 0.45034293, 0.50727217,

0.48425117, 0.49901586, 0.5117877 , 0.44626091, 0.49366251,

0.52250622, 0.47137421, 0.48823022, 0.46355799, 0.48297531,

0.45849614, 0.49826603, 0.5018006 , 0.53027553, 0.49104429,

0.53475808, 0.53419603, 0.51336594, 0.49737664, 0.44425113,

0.43717835, 0.48035877, 0.52054145, 0.48625197, 0.50322102,

0.5371977 , 0.49029784, 0.53773795, 0.49560237, 0.532912 ,

0.52124736, 0.48952215, 0.47378606, 0.52146146, 0.50099963,

0.54012174, 0.52125253, 0.48572131, 0.4737778 , 0.47305307,

0.45826967, 0.49166773, 0.50355952, 0.46341002, 0.51864045,

0.5396732 , 0.50692607, 0.48555718, 0.54058632, 0.52850325,

0.49126665, 0.53142638, 0.52608114, 0.51330806, 0.46695512,

0.43617527, 0.53669919, 0.4857681 , 0.49537785, 0.52160501,

0.50152158, 0.45031192, 0.5106592 , 0.52725318, 0.52884444,

0.55194157, 0.44346731, 0.50068734, 0.52517367, 0.49241824])

Parting Thoughts¶

- Python is a dynamically typed language with loads of built-in constructs

- Get used to types, functions, collections, loops, conditionals, and NumPy arrays

- Documentation is your friend, both as a consumer (Python docs, package readthedocs) and a creator (comments, type hints, good variable and function naming conventions)

- NumPy arrays in particular will be important going forward into machine learning

Questions?¶

References¶

- Mypy static type checker cheat sheet https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/cheat_sheet_py3.html